Last updated on June 27th, 2025 at 12:21 pm

Corfu’s Historic Milestones

Corfu’s History spans over 3,000 years and is both turbulent and fascinating.

Despite enduring numerous raids, attacks by barbarians, and conquests by Europeans during the medieval period, Corfu has managed to survive and maintain its Greek identity.

The island has successfully incorporated the best elements of civilizations that have left their mark on its culture throughout the centuries.

Mythology, Greek Colonization, and Roman Era

Prehistoric Times – Corfu in Mythology

Corfu has still inhabited since the Stone Age when it was mostly connected to the mainland. The present-day water body that separates it was once a modest lake until rising sea levels, triggered by melting glaciers around 10,000-8000 BCE, transformed Corfu into an island.

Evidence of Paleolithic life dots Corfu, with discoveries near Agios Mattheos in the southwest and Sidari in the northwest. Mythology adds flair to Corfu’s name, suggesting it stems from the nymph Corcyra, daughter of the river god Asopos, abducted by Poseidon and immortalized in the island’s nomenclature.

Mythical roots intertwine with historical narrative, introducing figures like Phaeakas and Nafsithoos, while Homer’s Odyssey brings King Alkinoos and his helpful daughter Nausikaa into the mix.

Corfu, identified as Scheria in Homer’s Odyssey, is the mythical island of the Phaeacians. These skilled seafarers are renowned for their magically swift ships, navigating without steering wheels.

When Odysseus arrives after numerous trials, King Alkinoos and his daughter Nafsika warmly welcome him. Odysseus recounts his adventures, impressing the king, who offers him a ship to aid his return to Ithaca.

The Phaeacians’ hospitality and advanced ships significantly aid Odysseus on his journey home, contributing a fantastical element to the epic tale.

A note of caution: Much of this tale resides in Greek mythology rather than historical certainty. The origin of the Phaeacians, tied to the Mycenaeans by Homer, lacks concrete evidence, as recent archaeological ventures haven’t unearthed Mycenaean relics on the island.

As centuries rolled on, Corfu became a melting pot, welcoming immigrants from Illyria, Sicily, Crete, Mycenae, and the Aegean islands, each contributing to the island’s evolving narrative.

The Ancient Times – the first Greek colonization

Around 775 BCE, the written history of Corfu officially begins with the arrival of Dorians from Eretria of Euboea. This initial settlement saw a significant boost in 750 BCE when Dorian refugees from Corinth, led by Hersikrates, established a robust colony.

Corinthian influence expanded, giving rise to colonies like Epidamnos in ancient Illyria (now Dyrrachium in Albania) and the city of Corfu in present-day Garitsa and Kanoni peninsula.

In 492 BCE, Corfu town, or Kerkyra in Greek, marked a milestone by being the first Greek city-state to build a fleet of triremes. The harbor, now the site of the modern airport, housed this formidable fleet, second only to Athens in ancient Greece, boasting over 300 triremes.

Corfu’s expansion led to a clash with Corinth, resulting in the first naval battle in 680 BCE. After the Corinthians’ failed attempt to occupy Corfu, the Athenians recognized the island’s naval strength and formed a defensive alliance, sending triremes for support.

This alliance endured through the Peloponnesian War, where Corfu actively supported Athenian interests. In 435 BCE, a Corinthian fleet of 150 ships challenged Corfu, but with Athenian assistance, the Corinthians retreated.

In 375 BCE, Corfu joined the Athenian Confederation, playing a role noted by historian Thucydides in the Peloponnesian War, contributing to Greece’s weakening and fracturing.

The war’s inevitability was rooted in Sparta’s concerns about Athens’ expansionist policies. Corfu’s history became intertwined with broader conflicts, leaving an indelible mark on the ancient Greek landscape.

First Roman era (229 BCE– 379 CE)

After the Peloponnesian War, internal conflicts between democrats and oligarchs weakened the state, leading to the dissolution of its alliance with Athens.

Illyrian pirates briefly took control, providing an opportunity for the Romans, who captured Kerkyra in 229 BCE. Granting autonomy to Corfiots, the Romans used the island as a naval base.

Corfu, like many Greek city-states, accepted Roman sovereignty for protection, becoming part of the Roman Empire.

In the first century CE, Christianity arrived, introduced by St. Paul’s disciples, Jason, and Sosipatros.

After Emperor Constantine died in 337 CE, the Roman Empire split into three sections. Corfu found itself in the Western Empire, covering Greece, Italy, and Rome’s African territories. The island’s history unfolded within this changing imperial landscape.

Medieval Times in Corfu’s History

Early Byzantine period (379 CE– 562 CE)

In 339 CE, during Emperor Theodosius’s reign, the Roman Empire was re-divided, placing Corfu in the Eastern Empire, also known as the early Byzantine Empire. This Byzantine period spanned around three centuries.

Sadly, this era was marred by Corfu’s susceptibility to frequent barbarian raids and pirate invasions. The island lacked sufficient protection, making it vulnerable to these threats, which significantly impacted the region during this time.

East Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire)

During the period from 562 CE to 1267 CE, Corfu underwent significant changes. In 562 CE, the island faced a devastating attack by the Goths, resulting in the destruction of the ancient city of Corfu, now known as Paleopolis.

This event marked the end of the ancient city and signaled the beginning of the medieval age on the island. The displaced inhabitants moved north to a natural promontory, forming the foundation for the old fortress. Over time, the new city expanded into what is now the old town of Corfu.

From 562 CE to 1267 CE, Corfu experienced the Byzantine period, followed by the challenging Angevin occupation. Positioned as the westernmost corner of the Byzantine Empire, Corfu faced constant pirate attacks and territorial ambitions from neighboring regions.

To safeguard Corfu, the multicultural Byzantine Empire took extensive measures. They stationed diverse mercenary guards, including Greeks, Syrians, Bulgarians, and stradioti (Byzantine soldiers), across the island. These guards, deployed from the northeast to the southwest, gradually assimilated into the local population.

This era witnessed the construction and enhancement of many fortresses on the island. The old Corfu fortress in the city underwent redesign and fortification. Other fortresses like Angelokastro in northwestern Corfu, Kassiopi, Gardiki in the southwest, and several smaller ones were built, bolstering the island’s defenses.

The turbulent years after the Fourth Crusade (1204 CE – 1214 CE)

In 1204 CE, the Normans of the Fourth Crusade captured Corfu. Shortly after, the Venetians took control, holding the island until 1214 CE.

This period marked a notable shift in Corfu’s history as it exchanged hands between these European powers.

The Despotate of Epirus (1214 CE – 1267 CE)

From 1214 to 1259 CE, Corfu became part of the Byzantine domain of Epirus, specifically the Duchy known as the Despotate of Epirus.

During this period, Despot Duke Michael-Angelos Komnenos the Second oversaw the construction of significant fortifications on the island. These included the Gardiki fortress, located near today’s Chalikouna area, and the Angelokastro fortress, situated in the northwest part of the island north of Paleokastritsa.

These fortifications played a crucial role in the island’s defense during this era.

The Period of Sicilian Rulers

During the tumultuous period from 1259 to 1267 CE, Corfu experienced various attempts by Sicilian rulers to gain control over the island, employing diplomatic means like dowries and, at times, resorting to military force.

The first successful conqueror of the island was Manfred, the king of Sicily. However, following Manfred’s death in battle, his Franco-Cypriot adjutant, named Philip Ginardo, took charge of Corfu.

Subsequently, Philip Ginardo met a violent end, leading the island to fall under the rule of his generals, the Garnerio brothers, and Thomas Alamano.

It is noteworthy that the surname “Alamanos” still exists in Corfu today, indicating a Sicilian origin for some of the island’s inhabitants.

The House of Anjou (1267 CE – 1386 CE)

In 1267 CE, the Angevin King of Sicily, Charles of the House of Anjou, successfully conquered Corfu. Upon securing control, he reorganized the island into four administrative regions: Gyrou, Orous, Mesis, and Lefkimi—names that endure in the region today.

This period saw a significant influx of Jewish people, mainly from Spain, settling in Corfu and establishing the Corfiot Jewish community.

Charles of Anjou also tried to replace the Orthodox Christian faith with Roman Catholicism, aiming to convert Orthodox churches. However, this endeavor proved unsuccessful and concluded when the Venetians regained control of the island.

The Venetian domination in Corfu, 1386 – 1797CE

Venetian Rule: Purchase and Unusual Resistance

During the Council of Corfu, a significant majority of the nobility favored Venetian protection due to the crumbling Byzantine Empire and the constant Turkish threat. In 1386 CE, the Council officially sought refuge with the Republic of Saint Markos (Venice).

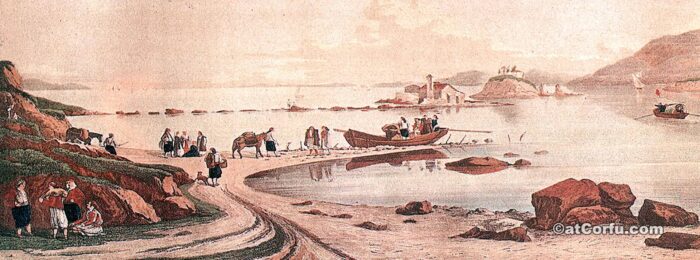

Recognizing Corfu’s strategic importance and agricultural potential, the Venetians purchased the island from the Kingdom of Naples for 30,000 gold ducats. Venetian forces, led by “Admiral of the Gulf” Giovanni Miani, landed in Corfu.

This turbulent time lacked a strong sense of national identity, leading to unusual events. While Venetians occupied the Old Fortress without resistance and dominated most of the island, the Angevin-controlled fortresses of Angelokastro and Kassiopi in the north opposed the sale. Residents, supporting the Angevins, fought against the Venetians.

In response, Venetians sent an army to capture both fortresses. Angelokastro surrendered quickly, but Kassiopi resisted fiercely. The Venetians, angered by this resistance, destroyed the Kassiopi fortress, leaving only remnants today.

This marked the start of the second extended period of Venetian rule in Corfu, lasting precisely 411 years, 11 months, and 11 days.

The constitution during the Venetian domination

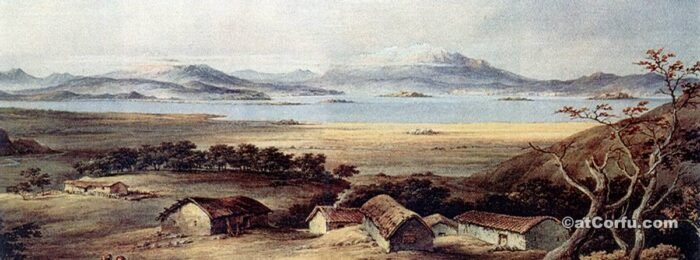

The Venetian rule in Corfu established a feudalistic system with three social classes: nobility, citizens (Civili), and poor people (called Popolari). The painting of medieval Corfu, now Evgenios Voulgaris Street, shows a snapshot of life, with little change over time.

Agriculture thrived with olive tree cultivation, and Corfu’s connections with great empires boosted arts and sciences. The Venetian era profoundly impacted Corfu, influencing art, music, culture, local language, cuisine, and architecture.

Corfu’s constitution during the Venetian occupation was exclusive, concentrating political power in the hands of the local nobility. Venetians with political influence included the General Proveditor of the Sea and his Judiciary. The Golden Book listed local nobles, granting privileges.

During the second Ionian state, only those in the Libro d’Oro enjoyed Liston area privileges. Originally, Byzantine names dominated, later joined by affluent civilians supporting the state treasury. Today, many city names trace back to this list, with a few from villages.

The migration flow from Turkish-occupied Greece

The Venetians, while securing Corfu city, struggled to protect the countryside, leading to tragedies during barbarian raids and pirate attacks, notably Turkish invasions in 1537 and 1571.

In 1537, the Turks invaded, capturing and selling 20,000 countryside men as slaves. Greeks from the Peloponnese, Epirus, and Crete migrated to Corfu, rebuilding the depopulated areas.

In 1571, Venetians lost the Peloponnese, Crete, and Cyprus, prompting a refugee influx to Corfu. The Venetians encouraged migration to repopulate and attract skilled individuals, weakening the Ottomans and strengthening Venice.

Refugees from Nafplio and Monemvasia settled in Lefkimi, Pirgi to Kassiopi, and south of Nissaki (Barbati), shaping the island’s demographics.

Peloponnesian immigrants founded Moraitika and Korakiana, contributing to the prevalence of surnames like Moraitis and “opoulos.”

Cretan immigrants impacted Garitsa, Saint Markos, Stroggyli, Messonghi, Argyrades, and Kritika, influencing Corfu’s linguistic idiom with unique pronunciations.

Despite these influences, Corfu’s culture remained resilient, incorporating new elements, and the immigrants eventually integrated into the Corfiots’ lives. In 1800, Souli refugees settling in Benitses became a significant part of the population after Ali Pasha’s destruction of Souli.

The Venetian fortifications and the frequent Turkish raids

The Venetians, unable to convert Corfu to Catholicism, prioritized political stability and coined the phrase “Siamo prima Veneziani e poi Cristiani” (We are first Venetians and then Christians). To promote harmony, they organized joint religious events for both Catholics and Orthodox Christians, continuing traditions today.

With public discontent due to Turkish threats, especially after losing Crete and Cyprus, Corfu became crucial to Venice. The Venetians, determined to fortify the island, undertook ambitious plans from 1576 to 1588.

They built the San Marcos fortress on the west hill, creating the vast Esplanade Square in front of the old fortress. Connecting them with a protective wall featuring bastions like Raimondo and St. Athanasius, they added gates like Porta Reale, Porta Raymonda, Gate of Spilia, and Gate of Saint Nicholas, enhancing defenses.

Engineers Michele Sanmicheli and Ferrante Vitelli designed these fortifications, evolving over the 17th century. After repelling the Turks in 1716, Marshal Johann Matthias von Schulenburg added another wall outside, designed by F. Verneda.

Post the 1716 Turkish invasion, Vido Island, Avrami and Saint Sotiros hills, and the San Rocco (Saroko) area were fortified, ensuring Corfu’s robust defense.

The Turkish Siege of 1716

The 1716 siege of Corfu marked a pivotal moment in the Seventh Venetian-Turkish War, with the island’s occupation viewed as a potential threat to Venice and Europe.

The Turkish forces, numbering 25,000-30,000, supported by 71 ships and about 2,200 guns, posed a formidable challenge. In contrast, the Venetians, with only 3,097 men (2,245 combatants), faced a significant numerical disadvantage.

Defending the Corfu New Fortress, Marshal Johann Mattias Von Schulenburg dealt with initial chaos among locals seeking refuge. He quickly recruited able-bodied individuals, bolstered reservists, and lifted the besieged morale.

Starting on July 8th and concluding after fierce battles on August 22nd, the siege witnessed a turning point on August 20th when a storm scattered Turkish ships, leading to significant losses. While Corfu credited St. Spyridon for the storm, military factors, including the Ottoman army’s defeat in Peterwardein, played a crucial role in the Turks’ retreat.

Casualties included around 800 dead and 700 wounded defenders, contrasting with substantial Turkish losses, totaling 6,500 men, including Muchtar, Ali Pasha’s grandfather.

A diverse coalition supported Corfu’s defense, comprising Venetians, Germans, Italians, Maltese, Papal, Genoese, Tuscan, Spanish, and Portuguese forces, showcasing the unity that secured victory.

Corfu’s Heroic Stand: Defying the Ottoman Tide in 1716

During the conflict, the Jewish community in the city exhibited remarkable courage, mobilizing under the leadership of the Rabbi’s son, equipped through the Corfiot Jewish community’s resources.

Antrea Pizanis, the General Proveditor of Corfu, commanded the light fleet and served as Marshal Schulenburg’s adjutant. The key role played by Corfiot Lieutenant Dimitrios Stratigos added to the cohesive defense.

Marshal Schulenburg’s unwavering determination earned him a lifelong pension from the Senate of Venice, with his statue adorning the Old Fortress entrance.

All those who displayed bravery in the conflict received due recognition and honors.

The Turkish setback in Corfu held historic significance, altering the trajectory of Europe’s history, especially for Greece. The bravery of the Corfiots and Europeans played a crucial role in preventing the potential expansion of the Ottoman Empire and influencing the emergence of the Greek nation.

Unfortunately, this event often goes unrecognized by historians, despite its pivotal role in shaping the present-day Greek state. The successful repulsion of the Turkish invasion in 1716 carried great importance for Western Europe, marked by grand celebrations and even inspiring Antonio Vivaldi’s oratorio “Juditha Triumphans,” performed in major theaters for years.

This event marked the final Turkish attempt to expand into Europe.

The Venetian era, while leaving positive cultural legacies, faced challenges such as strained relations between commoners and the nobility. Uprisings, particularly in villages, resulted from the Venetian ruling class’s authoritarianism and arbitrary behavior.

Corfu remained a significant part of the Venetian State until the fall of Venice to the French, showcasing its enduring importance to Venice.

Modern Times

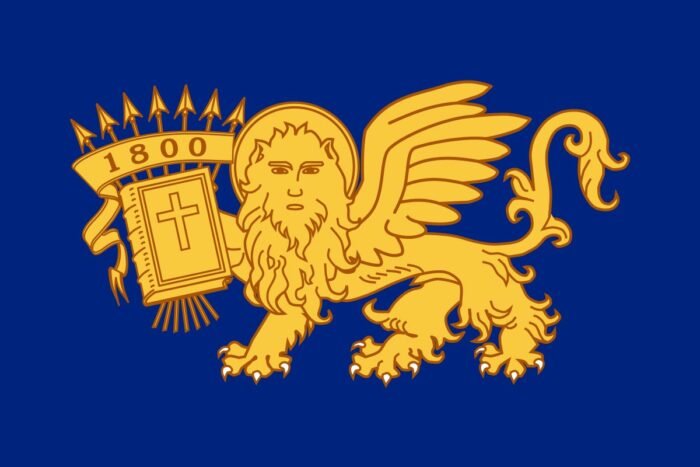

The Ionian State (Septinsular Republic) 1800-1807

The Venetian era gave way to the first French occupation in 1797, marking the end of the feudal system as the people symbolically burned the Book of Gold (Libro d’oro) containing the aristocrats’ names across the Ionian islands.

Initially welcomed as liberators, the French presence soon led to distress due to their arrogance and heavy taxation, causing a shift in public sentiment.

The period was marked by instability, with the populace divided. Exploiting discontent, the Nobles conspired to have Corfu occupied by the Russians, succeeding in 1799.

Russian Admiral Ousakof reinstated noble privileges, and on March 21, 1800, at Ioannis Kapodistrias’ urging, the Ionian State, or the Septinsular Republic, emerged. This marked the birth of the first independent Greek state, a vision Kapodistrias saw as a precursor to Greece’s rebirth.

The Ionian State, a federation of seven larger island states, persisted until 1807 when the French, under Napoleon, returned and remained until 1814. During this period, Liston’s iconic buildings were constructed by the French for military use.

United States of the Ionian Islands 1815-1864

In 1815, Corfu fell under British rule, and the seven Ionian Islands declared independence under British protection, forming the “United States of Ionian Islands” with Corfu as the capital.

Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Maitland became the first “Lord High Commissioner.” The government had 29 members, with 7 from Corfu, Kefalonia, and Zante, and 4 from Lefkada. Paxos, Ithaka, and Kythera each elected 1 member, with a rotating second member.

During this period, institutions like the Ionian Academy, Reading Society, and public library were established. The local economy flourished, witnessing the construction of the Palace of Saint Michael and George, expanded road networks, and the aqueduct supplying water to Corfu town from the hills around Benitses.

Power plants were built, though later moved to Piraeus after the union with Greece. The British era also saw improvements to the island’s infrastructure, and immigrants from Malta, the original home of many Corfiots, arrived during this time.

Ioannis Kapodistrias and his role in the History of Corfu

Ioannis Kapodistrias, the first governor of modern Greece, was born on the island into an aristocratic family. After pursuing education, he rose to prominence in Russia, eventually becoming a foreign minister and actively participating in European political affairs.

His notable achievements included contributions to the formation of Switzerland’s state entity and constitution, earning him recognition from the Swiss.

While Kapodistrias had limited involvement in Corfu’s historical course, playing a diplomatic role in its liberation from French rule by a Russian-Turkish alliance in 1800, his overall connection with the island’s history is not extensive. Despite his ties to Corfu being somewhat limited, his diplomatic contributions are worth acknowledging.

(Note: Historical alliances between Russia and Turkey, despite fluctuations, have been observed in various instances. This might be relevant for those with an affinity for Russia.)

Union with Greece

On May 21, 1864, a pivotal moment occurred as Corfu and all the Ionian islands united with Greece following the London treaty and a favorable vote from the Ionian Parliament.

This marked a significant turning point in Corfu’s history, signifying the end of its tumultuous past and the decline of its status as the capital of the Ionian State. The emerging Greek state, grappling with limited resources, couldn’t sustain two centers of economic and cultural influence. Consequently, in the competition with Athens, Corfu lost its university, prestige, and cultural prominence, transforming into a Greek provincial town within just 40 years.

Nevertheless, the memories of its glorious past endure, making Corfu a unique Greek town that distinguishes itself from others.

Influences from Corfu’s conquerors

Corfu’s cultural identity stands out in Greece due to its long association with Venice, distinct from much of Greece influenced by the Ottoman Empire.

Venetian rule for over four centuries deeply influenced the island’s architecture, cuisine, and music.

This heritage is visible in Corfu’s diverse architectural styles, culinary traditions, and unique musical heritage, reflecting a blend of Greek, Roman, and Venetian legacies.

The Venetian era fostered a cultural orientation towards the West, setting Corfu apart from mainland Greece’s Eastern influences.

Today, Corfu’s rich cultural tapestry showcases its unique historical journey amidst a picturesque Mediterranean backdrop.

Summary

Throughout its history, Corfu has been a crossroads of cultures, blending Greek, Venetian, French, and British influences into its architecture, cuisine, and traditions.

Today, it remains a popular destination known for its natural beauty, historical sites, and vibrant culture.

More in Corfu’s History

Corfu: Union With Greece and Modern Times

On the 21st of May 1864, the British ruled Corfu and together with all the Ionian Islands, following the London Agreement and the Ionian Parliament’s resolution, united with Greece

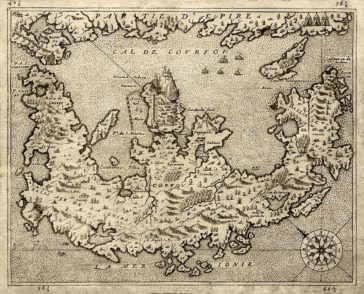

Corfu of the Middle Ages on a Map of 1575

This map of Corfu of 1575 was designed like all medieval maps. According to the sources of that time and lots of imagination

Corfu at Prehistoric and Ancient Times

Corfu has been inhabited since the Stone Age.

At that time it was part of the mainland and the sea that today separates it from the mainland was only a small lake

Roman Era and Early Byzantine Period

At the time of emperor Theodosius (339 AD), the Roman empire was re-divided into east and west, Corfu then belonged to the east empire

Corfu Middle Ages and Byzantine Period

During this period the whole island was exposed to frequent barbarian raids and pirate invasions

Venetian Domination in Corfu

The Council of Corfu and especially the overwhelming majority of nobility were friendly with the Venetians

Comments