Last updated on October 28th, 2025 at 12:40 am

1. Introduction to Greek Mythology and Its Importance

Greek mythology is one of the richest and most influential mythological systems in human history.

It is a complex web of stories, traditions, and religious beliefs in the area of today’s Greece, developed by the ancient Greeks over centuries, from the Bronze Age through the Classical period and beyond.

These myths explain the origins of the universe, the lives and adventures of gods and heroes, and the nature of humanity and the cosmos.

Origins and Development

The roots of Greek mythology can be traced back to several ancient cultures, particularly the Minoan civilization on Crete (circa 3000–1450 BCE) and the Mycenaean civilization (circa 1600–1100 BCE). Archaeological evidence, such as frescoes, pottery, and tablets, suggests that many of the stories and deities in classical Greek mythology have older antecedents from these Bronze Age societies.

For centuries, these myths were preserved and passed down orally, long before poets like Homer and Hesiod codified them in writing around the 8th century BCE. These poets did more than entertain—they organized and interpreted the myths, shaping the framework that defines Greek mythology today.

Much of what we know comes from their epic poems: Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and Hesiod’s Theogony and Works and Days. Later writers provide only minor references, mostly confirming the accounts of these foundational sources.

Influence Through the Ages

Greek mythology influenced Greek life in art, literature, politics, and religion, and its legacy continues to shape Western culture and modern storytelling.

The Challenge of Greek Mythology

Greek mythology is not a single, uniform story. Instead, it’s a vast and sometimes contradictory tapestry of myths, versions, local traditions, and later reinterpretations.

This complexity makes it challenging to study but also endlessly fascinating.

Understanding Greek mythology requires exploring its multiple layers: the divine (gods and goddesses), the mortal (heroes and humans), the monstrous (creatures and forces of chaos), and the cultural (rituals and societal norms).

It’s a window into how the ancient Greeks made sense of their world — a mix of wonder, fear, and awe.

Greek Mythology

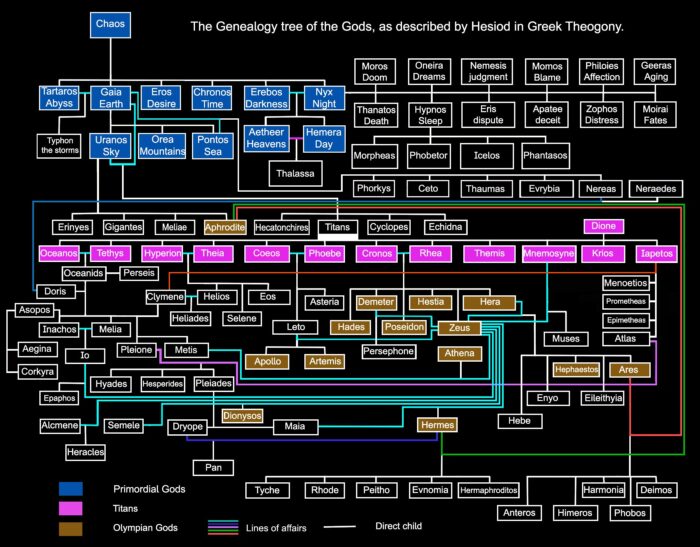

2. Creation Myths and Hesiod’s Theogony

The Birth of the Cosmos and the Gods

Greek mythology opens with cosmogonic and theogonic myths explaining the universe’s origin, the birth of the gods, and humanity’s place in the divine order. Central to this is the transition from primordial Chaos—a formless void—to an ordered cosmos governed by the Olympian gods.

Theogony: Genealogy of the Gods

Primordial Deities: Foundations of the Cosmos

In the earliest cosmogonies, three fundamental forces existed from the beginning: Chaos (the void), Chronos (Time, representing the eternal flow, not to be confused with Cronos the Titan), and Anangke (Necessity, the inexorable force of fate).

These primal entities set the stage for the creation of the cosmos, shaping the emergence of Gaia (Earth), Ouranos (Sky), and the first Primordial deities and natural forces through divine births.

Other primordial beings include:

- Gaia (Earth): The solid foundation and mother of all life.

- Uranus (Sky): The vast sky and consort of Gaia.

- Tartarus: The deep abyss beneath the earth.

- Eros: The creative force of love and procreation.

- Nyx (Night): Personification of night and darkness.

- Erebus (Darkness): The embodiment of deep shadow and gloom.

The establishment of cosmic order replaces primordial chaos.

📌 Read everything about Theogony in Greek Mythology

The Foundation of the Greek Mythical Worldview

These cosmogonic and theogonic narratives form the backbone of Greek mythology by:

- Explaining the universe’s origin and divine hierarchy.

- Depicting humanity’s creation, fall, and renewal.

- This framework sets the stage for the complex stories of gods, heroes, and mortals that define Greek myth.

3. The Rise of Titans and Cronus: The Titanomachy Prelude

The Titans were the second generation of divine beings, born from Gaia (Earth) and Uranus (Sky). They ruled during the Golden Age, a time of relative peace and prosperity before the Olympian gods took over.

The Titans

- Oceanus (Ocean)

- Coeus

- Crius

- Hyperion

- Iapetus

- Cronus (Saturn in Roman)

- Theia

- Rhea

- Themis

- Mnemosyne

- Phoebe

- Tethys

Second Generation Titans (Children of the First Generation Titans):

- Helios (son of Hyperion & Theia), the Greek name of the Sun

- Selene (daughter of Hyperion & Theia), the Greek name of the Moon

- Eos (daughter of Hyperion & Theia)

- Astraeus (son of Crius & Eurybia)

- Pallas (son of Crius & Eurybia)

- Perses (son of Crius & Eurybia)

- Atlas (son of Iapetus & Clymene/Asia)

- Prometheus (son of Iapetus & Clymene/Asia)

- Epimetheus (son of Iapetus & Clymene/Asia)

- Menoetius (son of Iapetus & Clymene/Asia)

- Leto (daughter of Coeus & Phoebe)

- Asteria (daughter of Coeus & Phoebe)

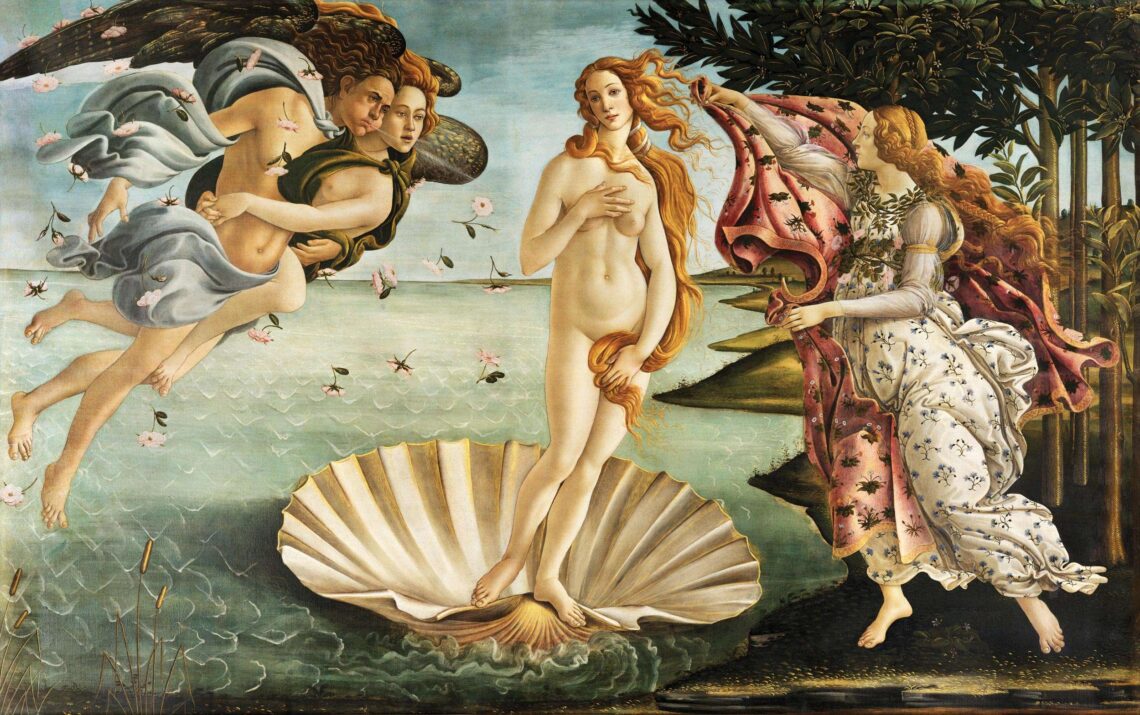

According to Hesiod, the Olympian goddess Aphrodite was a Titaness, as she was born from the genitals of Uranos, when Cronos threw them into the sea.

Cronus and the Overthrow of Uranus

Uranus imprisoned some of his children (Cyclopes and Hecatoncheires) in Tartarus, angering Gaia.

Gaia gave his son Cronus a sickle to castrate Uranus, overthrowing him and ending his reign.

Cronus then ruled as the chief Titan but feared a prophecy that his children would overthrow him.

The Titanomachy: War of the Titans and Olympians

To prevent the prophecy, Cronus swallowed his children at birth.

Rhea, Cronus’s wife, hid their youngest child, Zeus, saving him from this fate.

Zeus grew up secretly and led a revolt against the Titans.

The war, the Titanomachy, lasted ten years.

With the help of the Cyclopes (who forged Zeus’s thunderbolts) and the Hundred-Handers, the Olympians defeated the Titans.

The Titans were cast into Tartarus, guarded by Hecatoncheires, imprisoned by the new Olympian order.

Symbolism of the Titans

Represent the raw, primal forces of nature.

Their defeat symbolizes the transition from chaotic, natural rule to civilized order under the Olympian gods.

The cycle of overthrow echoes throughout mythology—father replaced by son—a motif of change and succession.

The Gigantomachy and Other Battles

The struggle didn’t end there. The Olympians fought other foes:

The Gigantomachy is a battle against the Giants born from Gaia to challenge Zeus.

The Typhon, a monstrous serpent-like giant born of Gaia and Tartarus, nearly overthrew Zeus.

These myths symbolize the constant tension between order and chaos, civilization and nature.

The Flood of Deucalion: Humanity’s Renewal

In the interlude between the fall of the Titans and the rise of the Olympians, Zeus judged humanity’s wickedness with a great flood.

He sends a devastating flood to cleanse the earth.

Deucalion and Pyrrha were the sole survivors who built an ark, after Prometheus‘ warning, to escape the deluge.

Repopulation: After the flood, they throw stones over their shoulders, which transform into new humans, symbolizing rebirth and renewal.

This establishes the mythic roots of the Greek people and their connection to the gods.

Hellen and the Origin of the Hellenes

Hellen: Son of Deucalion and Pyrrha, regarded as the mythic ancestor of the Hellenes.

Hellen’s Sons:

Dorus: Founder of the Dorians.

Xuthus: Father of the Ionians and Achaeans (through his sons Ion and Achaeus).

Aeolus: Founder of the Aeolians.

Through Hellen and his sons, the ancient Greeks traced their tribal origins and identity, grounding their heritage in mythic history.

📌 Is Mythology The Distorted History Of The Greek Dark Ages?

4. The 12 Greek Gods of the Olympian Pantheon

- Dias (Zeus) – King of the gods, ruler of sky and thunder. The Greek name of Jupiter.

- Hera – Queen of the gods, goddess of marriage and family.

- Poseidon – God of the sea, earthquakes, and horses. The Greek name for Neptune.

- Dimitra (Demeter) – Goddess of agriculture and harvest.

- Athena – Goddess of wisdom, warfare, and crafts.

- Apollon (Apollo) – God of the sun, music, prophecy, and healing.

- Artemis – Goddess of the hunt, wilderness, and childbirth.

- Ares – God of war and battle frenzy. The Greek name for Mars.

- Aphrodite – Goddess of love, beauty, and desire. The Greek name for Venus.

- Hephaestos – God of fire, metalworking, and craftsmanship.

- Hermes – Messenger of the gods, god of communication and travel. Greek name for Mercury.

- Hestia – Goddess of hearth and home.

- Dionysos – God of wine, ecstasy, and revelry.

- Hades – God of the underworld and the dead. Also known as Plouton (Pluto in Latin)

📌 For detailed stories and myths about these gods, visit our 12 Greek Gods Pantheon page.

📌 Read about Zeus’ notorious personal life and countless affairs

📌 Read about Ancient Goddesses: Powerful Women in Greek Mythology

📌 Read about the Mythology of the Ionian Islands: Odysseus, Poseidon, and Lost Kingdoms

Lesser Deities and Spirits

Beyond the Olympians, the Greek divine world includes many minor gods and personifications:

- Eros: God of love and attraction.

- Nike: Goddess of victory.

- The Muses: Nine goddesses inspiring arts and sciences.

- The Fates (Moirai): Controllers of destiny.

- Nemesis: Goddess of retribution.

Each minor deity personifies key aspects of the human experience or natural phenomena, enriching the mythological tapestry.

5. Tales and Myths: The Divine and Mortal Drama

Greek mythology is rich with timeless stories where gods and mortals cross paths—sometimes in harmony, often in conflict. These myths explore love, betrayal, pride, fate, and transformation, leaving a legacy of heroes, tragic figures, and moral lessons.

📌 Explore the most famous Greek myths — from Prometheus stealing fire to the abduction of Persephone — in our dedicated Greek Mythology Tales section.

Themes and Dynamics in Mortal-God Relationships

- Favor and Punishment: Mortals can receive divine blessings or curses based on their behavior.

- Love and Desire: Gods often pursue or intervene in mortal romances, sometimes benevolently, sometimes destructively.

- Heroism and Sacrifice: Many heroes have divine parentage or assistance, but must struggle with mortal limitations.

- Fate vs. Free Will: Prophecies and divine will often shape mortal lives, yet human choices matter.

- Transformation and Metamorphosis: Mortals are often transformed—into animals, plants, or stars—as reward or punishment.

Why These Tales Matter

These stories humanize the gods and elevate mortals, showing the messy, passionate interplay of divine and human worlds. They’re the source of timeless narratives that still resonate in literature, psychology, and culture today.

The Purpose and Function of Myths

Greek myths were far more than fanciful stories. They functioned as:

Explanations of the natural world: Myths explained why natural phenomena occur, such as thunderstorms (Zeus’s thunderbolts), the changing seasons (Persephone’s descent and return), or the origin of rivers and mountains.

Religious foundations: They established the pantheon of gods and their relationships to humans, legitimizing rituals, sacrifices, and festivals.

Cultural identity: Myths reinforced social values, customs, and the political order, often linking local populations to divine ancestry or heroic founders.

Moral and philosophical lessons: Many myths conveyed lessons about hubris, justice, fate, and human limitations, often warning about the consequences of defying the gods.

6. Great Heroes and Their Quests

The Concept of the Hero in Greek Mythology

Greek heroes are far from flawless; they embody strength, courage, wit, and honor, but also hubris, flaws, and vulnerability. Heroes often serve as intermediaries between gods and humans — champions favored by the gods but still subject to fate and mortality.

The hero’s journey frequently involves daunting tasks, battles with monsters, quests for glory, or journeys of transformation.

Heracles (Hercules) — The Archetypal Hero

Heracles is perhaps the most famous Greek hero, known for his incredible strength and the Twelve Labors he performed as penance for killing his own family in a madness sent by Hera.

📌 All 12 labors of Heracles, described in detail

The Twelve Labors:

- Slay the Nemean Lion — a beast with impenetrable skin.

- Slay the nine-headed Lernaean Hydra.

- Capture the Golden Hind of Artemis.

- Capture the Erymanthian Boar.

- Clean the Augean stables in a single day.

- Slay the Stymphalian Birds.

- Capture the Cretan Bull.

- Steal the Mares of Diomedes.

- Obtain the girdle of Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons.

- Capture the cattle of the monster Geryon.

- Steal the apples of the Hesperides.

- Capture and bring back Cerberus, the three-headed dog guarding the underworld.

Heracles’ labors symbolize human struggle against seemingly impossible odds, the quest for redemption, and the pursuit of immortality through glory.

Perseus — Slayer of Medusa

Perseus, son of Zeus and the mortal Danaë, is famous for beheading Medusa, a Gorgon whose gaze turned people to stone. With gifts from the gods — winged sandals, a reflective shield, and Hades’ helm of invisibility — he overcame numerous dangers.

He also rescued Andromeda from a sea monster, further cementing his status as a savior and hero.

Theseus — Founder and Protector of Athens

Theseus is celebrated as a founding hero of Athens. His most famous feat is navigating and defeating the Minotaur in King Minos’s labyrinth on Crete, aided by Ariadne’s thread.

He embodies intelligence, bravery, and civic duty, representing the triumph of order and civilization over barbarism.

Jason and the Argonauts — The Quest for the Golden Fleece

Jason’s quest for the Golden Fleece involved assembling a band of heroes — the Argonauts — including Heracles, Orpheus, and Atalanta. Their journey was fraught with monsters, gods’ interference, and treachery.

Jason’s story blends adventure, loyalty, betrayal, and tragedy, highlighting the complexities of heroic endeavors.

Achilles — The Greatest Warrior of the Trojan War

Achilles, son of the sea nymph Thetis and mortal Peleus, was nearly invincible due to being dipped in the River Styx, except for his heel.

His rage and fate form the core of Homer’s Iliad, which explores themes of honor, mortality, wrath, and the human cost of war.

Other Notable Heroes

- Odysseus — Known for his cunning and endurance in the long journey home from Troy, recounted in the Odyssey.

- Bellerophon — Rider of Pegasus who defeated the Chimera.

- Atalanta — A fierce huntress and one of the few female heroes.

- Orpheus — Legendary musician who ventured into the underworld to retrieve his wife.

Themes Explored in Heroic Myths

- Fate vs. Free Will: Many heroes struggle against predetermined destiny.

- Hubris and Nemesis: Excessive pride often leads to downfall.

- Mortality and Immortality: The quest for eternal glory or literal immortality.

- Divine Favor and Wrath: The gods’ support or anger profoundly affects heroes’ fates.

Heroic myths illustrate human aspiration, frailty, and the quest for meaning in a world governed by divine forces and fate.

📌 Great Heroes in Greek Mythology and Their Labours

7. Monsters and Mythical Creatures

Monsters often personify chaos, danger, or divine punishment. They’re obstacles to be overcome, tests of heroism, or warnings about hubris and human limits. Some are purely destructive; others are liminal, existing between worlds or embodying transformation.

Typhon: The Monster at the Abyss — A Deep Dive

In the vast and wild tapestry of Greek mythology, few figures embody chaos and destruction as fiercely as Typhon, the monstrous storm giant born of Gaia and Tartarus.

His sheer power and terrifying form—part serpentine, part human, with hundreds of dragon heads—marked him as the ultimate challenge to the gods and the order they sought to maintain.

Though Typhon himself was defeated by Zeus in a cataclysmic battle that shook the very foundations of the cosmos, his legacy did not end with his fall.

From the depths of this primal chaos came a terrifying brood of offspring, creatures as fearsome and wild as their father, each carrying a fragment of his destructive power.

📌 Meet the 6 mighty monsters of Greek mythology

📌 See everything about the mighty Typhon

Echidna and the Monstrous Lineage: The Source of Greek Myth’s Darkest Beasts

Echidna: The Mother of Monsters — Deep Profile

Origins and Description

Echidna’s origins are somewhat obscure and vary by source, reflecting her liminal nature. In the Hesiodic tradition, she is often described as the daughter of Phorcys and Ceto, primordial sea gods embodying hidden dangers and the unknown depths—perfect parents for a creature who bridges human and monster.

- Upper body: Often described as a beautiful woman, but with fierce, monstrous features.

- Lower body: A massive serpent or dragon tail, scaly and sinuous.

- Habitat: Dwells in caves, deep forests, or other wild, untamed places, far from human civilization.

Symbolism of Echidna

Echidna embodies the uncanny: a mix of attraction and repulsion. She is both mother and monster, symbolizing nature’s fecundity and its danger.

The Brood of Chaos: Echidna and Typhon’s Children

Orthrus: The Two-Headed Guard Dog

Orthrus is Cerberus’s sibling and guard dog to King Geryon’s cattle.

- Role: Slain by Heracles during his tenth labor.

- Symbolism: Represents vigilance and the protection of valuable resources.

Cerberus: The Three-Headed Guardian of the Underworld

Cerberus is the monstrous dog with three (sometimes more) heads tasked with guarding the gates of the Underworld.

- Physical description: A massive beast with a serpent for a tail and sometimes snakes growing from its back.

- Mythic role: Embodies the boundary between life and death.

- Notable myths: Heracles captured Cerberus alive without weapons—a symbolic conquest of death itself.

Hydra of Lerna: The Regenerating Serpent

The Hydra is a multi-headed serpent with regenerative abilities—cutting off one head causes two more to grow.

- Habitat: Lived in a swamp near Lake Lerna.

- Heracles’ labor: Heracles defeated the Hydra with Iolaus’s help, using fire to stop regrowth.

Chimera: The Fire-Breathing Hybrid

A creature composed of a lion’s head, a goat’s body, and a serpent’s tail.

- Mythic significance: Bellerophon, aided by Pegasus, slays the Chimera.

Sphinx: The Riddle-Master

A creature with a woman’s head, lion’s body, and sometimes a bird’s wings.

- Role: Guarded Thebes, posing riddles to travelers.

- Famous story: Oedipus solved her riddle, freeing Thebes from her curse.

Nemean Lion: The Invulnerable Beast

The Nemean Lion terrorized the region around Nemea and had impenetrable skin. Heracles killed the lion and wore its hide as armor.

Monsters as Mirrors of Humanity

Greek monsters aren’t just creatures to fight—they reflect human fears, instincts, and the chaotic forces that challenge civilization. They embody the struggle between order and chaos, courage and fear, morality and hubris.

Echidna and Her Progeny

Echidna, both life-giver and terror, symbolizes the duality of motherhood and monstrosity. Her children—Cerberus, the Chimera, the Hydra—often serve as trials for heroes, testing strength, wit, and virtue. Heroes like Heracles, Perseus, and Bellerophon confront these monsters to prove themselves.

Other Notable Monsters

- Medusa & the Gorgons: Mortality, danger, and female power.

- Minotaur: Human-animal hybrid, a labyrinthine obstacle.

- Cyclopes: Divine craftsmen, one-eyed giants.

- Sirens: Lure of desire and peril.

- Harpies, Satyrs, Nymphs, Centaurs: Various embodiments of nature, chaos, or primal instincts.

Symbolism and Function

Monsters often serve as:

- Barriers to progress: Challenges that heroes must overcome.

- Personifications of fears: Natural disasters, death, the unknown.

- Moral lessons: Punishing hubris, greed, or wickedness.

- Liminal figures: Blurring lines between human, animal, and divine.

Greek monsters make myths thrilling, but they’re also a lens to explore the human condition, civilization, and the eternal dance with chaos.

📌 Figures of Greek Mythology: Gods, Heroes & Monsters

Cultural and Psychological Interpretations

The Monster as a Mirror of Humanity

Echidna and her children are not just external monsters; they symbolize internal human fears and the wild instincts lurking beneath civilization’s surface. They challenge heroes and, through defeat or negotiation, reveal human resilience and limits.

Motherhood and Monstrosity

Echidna’s dual nature, beautiful yet monstrous, reflects ancient tensions about fertility, motherhood, and the fear of the unknown. She is a paradox: life-giver and source of terror.

The Monstrous Feminine

Many of Echidna’s children, and Echidna herself, relate to the concept of the monstrous feminine—female figures whose power and autonomy challenge patriarchal norms, often cast as dangerous or uncanny.

The Role of Echidna’s Progeny in Heroic Narratives

- Heroes often face Echidna’s offspring as trials testing their worthiness: Heracles’ twelve labors include slaying or capturing these monsters.

- Perseus defeats Medusa, using divine gifts and cunning.

- Bellerophon tames Pegasus to defeat the Chimera.

- Orpheus, Jason, and other heroes confront various monstrous challenges linked to this lineage.

Echidna and Typhon’s monstrous family forms the dark backbone of Greek mythology, embodying chaos, danger, and the wild forces that threaten human order.

Their stories are more than entertainment; they’re cultural metaphors about the human condition, civilization, and the eternal struggle between order and chaos.

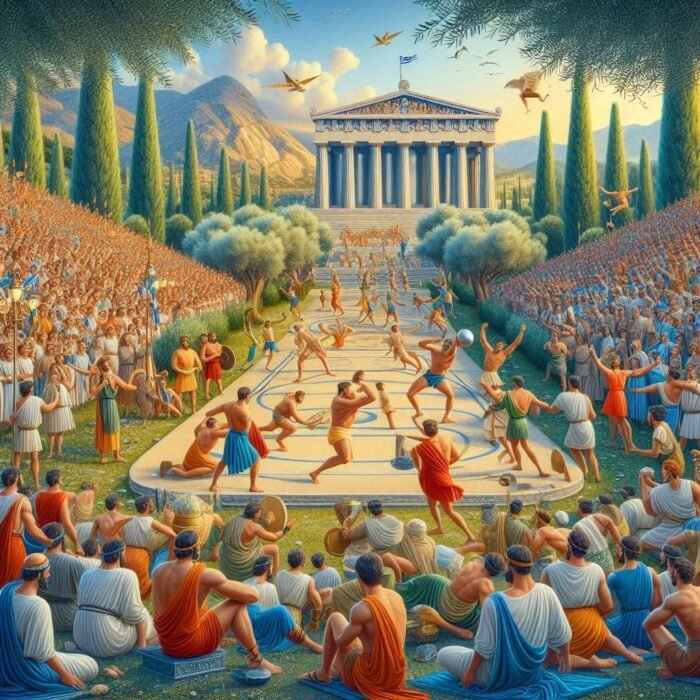

8. Ancient Greek Mythology in Society: Rituals, Festivals, and Cult Worship

Why Mythology Was More Than Stories

In ancient Greece, myths weren’t just entertainment or moral lessons—they were the framework for understanding the world, explaining natural phenomena, human nature, and the divine. They shaped religion, politics, social order, and identity.

The gods and heroes of myth were actively worshiped and honored through rituals and festivals, forming the core of communal life and cultural expression.

Sacrifices and Offerings

Sacrifices were the primary way to communicate with gods—offering animals (bulls, sheep), food, wine, and precious goods.

These acts were meant to appease the gods, gain their favor, or thank them for blessings.

Public sacrifices were grand events involving prayers, songs, and communal feasts.

Major Festivals

- Olympic Games (Honoring Zeus): Held every four years at Olympia.

- Combined athletic competitions, religious ceremonies, and sacrifices: Served as a unifying event for the Greek city-states.

- Panathenaia (Honoring Athena): Athens’ grandest festival, celebrating Athena’s birthday, included processions, sacrifices, and musical and athletic contests.

- The Peplos, a specially woven robe, was presented to Athena’s statue.

- Dionysia (Honoring Dionysus): Celebrated the god of wine and theater.

- Featured dramatic competitions: Including tragedies and comedies, symbolized fertility, ecstasy, and the breaking of social norms.

- Eleusinian Mysteries (Honoring Demeter and Persephone): Secret initiation ceremonies promise knowledge of life after death, symbolizing the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. One of the most important religious rites in Greece.

Note: Though these festivals are historical religious practices, they are deeply inspired by the myths and stories of Greek mythology, weaving divine tales into the cultural fabric of ancient Greece.

Oracles and Prophecy

Oracles were sacred sites where gods communicated their divine will.

- Oracle of Delphi: Dedicated to Apollo; priestesses delivered cryptic prophecies.

- Oracle of Dodona: Devoted to Zeus and Dione; messages interpreted from rustling oak leaves.

- Oracle of Trophonius: Located in Boeotia; famous for mysterious underground rituals.

- Oracle of Ammon: Situated in Libya; combined Greek and Egyptian traditions.

City-states and individuals consulted these oracles before major decisions, highlighting the deep connection between prophecy, religion, and politics in ancient Greece.

Role of Myth in Social and Political Life

Myths legitimized political power and social customs—rulers often traced lineage to gods or heroes.

Myths reinforced moral codes and social roles, e.g., the sanctity of marriage, hospitality, and justice.

Festivals and myths strengthened community identity and unity.

📌 The Olympic Games in Ancient Greece

Mystery Cults and Personal Religion

Aside from public worship, Greeks participated in mystery cults that offered secret knowledge and personal salvation.

Cults of Orpheus, Eleusis, Dionysus, and others promised a closer connection to the divine.

These cults influenced later religious developments, including early Christianity.

Myth in Art and Literature

Myths were depicted everywhere—from vase paintings and sculpture to epic poems and drama.

Plays by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides dramatized myths, exploring human nature and divine will.

This made myths accessible and continually relevant.

Mythology’s Enduring Legacy

Ancient Greek mythology shaped Western culture’s foundations—art, literature, psychology, philosophy, and even modern storytelling. Understanding how deeply these myths were embedded in daily life gives insight into their power and endurance.

After exploring the rich tapestry of gods, heroes, and monsters, it’s worth stepping back to see how these myths shaped the daily life, beliefs, and culture of ancient Greece—and how their legacy continues to influence us today.

9. Greek Mythology’s Influence on Modern Culture and Thought

The Endless Well of Inspiration for Arts and Literature

Greek myths have been a creative goldmine for artists, writers, and musicians for over two millennia:

- Renaissance Art: Masters like Michelangelo and Botticelli revived mythological themes, depicting gods, heroes, and monsters with dramatic flair.

- Literature: From Shakespeare to James Joyce, Greek myths provide archetypes and stories that explore human nature, fate, and morality.

- Opera and Music: Composers like Monteverdi and Strauss created works based on mythic tales (e.g., Orpheus and Eurydice).

- Film and TV: Modern retellings—from Disney’s Hercules to blockbuster epics—keep myths alive and evolving.

- Psychology: Jungian Archetypes and Myth

Carl Jung viewed myths as expressions of universal archetypes residing in the collective unconscious:

The Hero’s Journey (Joseph Campbell expanded this from myths worldwide) is rooted heavily in Greek heroic narratives like those of Odysseus and Heracles.

Archetypes like the Wise Old Man (e.g., Zeus), the Trickster (Hermes), and the Great Mother (Demeter/Echidna) are psychological templates for human experience.

Myths help individuals understand internal conflicts, growth, and transformation.

Language and Expressions

Greek mythology has gifted us with a vast array of words and phrases embedded in modern language:

- Narcissism: From Narcissus, the youth obsessed with his reflection.

- Titanic: From Titans, meaning colossal or powerful.

- Herculean: Refers to tasks requiring great strength or effort.

- Pandora’s Box: Symbolizes unleashing unforeseen troubles.

- Achilles’ Heel: Denotes a critical weakness.

Philosophy and Moral Inquiry

Greek myths often served as a starting point for philosophical debates on fate, free will, and ethics:

Philosophers like Plato and Aristotle analyzed mythic themes to explore virtue and the nature of the divine.

Myths allowed exploration of human nature’s complexities, such as justice, hubris, and suffering.

Modern Storytelling and Popular Culture

The structure of myths influences modern storytelling, especially fantasy and adventure genres.

Characters inspired by Greek myths appear in comics, video games, novels, and TV shows, often reimagined to fit contemporary values.

Mythic motifs like the underworld journey, transformation, and divine intervention persist in narratives worldwide.

Scientific and Astronomical Legacy

Many planets, moons, stars, galaxies bear names from Greek mythology (e.g., Jupiter/Zeus, Titan, Galaxy, Uranus, Helios, Andromeda, Pluto, Charon…countless).

Mythical figures often serve as inspiration for naming biological species, scientific phenomena, and inventions.

Education and Cultural Identity

Greek mythology remains a staple of education worldwide, teaching language, history, ethics, and cultural literacy.

It connects us to the ancient world, influencing Western cultural identity and heritage.

📌 Find Beautiful Baby Names Inspired by Greek Mythology

The Eternal Dialogue Between Past and Present

Greek mythology acts as a living conversation across centuries, constantly reinterpreted and reinvented to address timeless questions and new challenges.