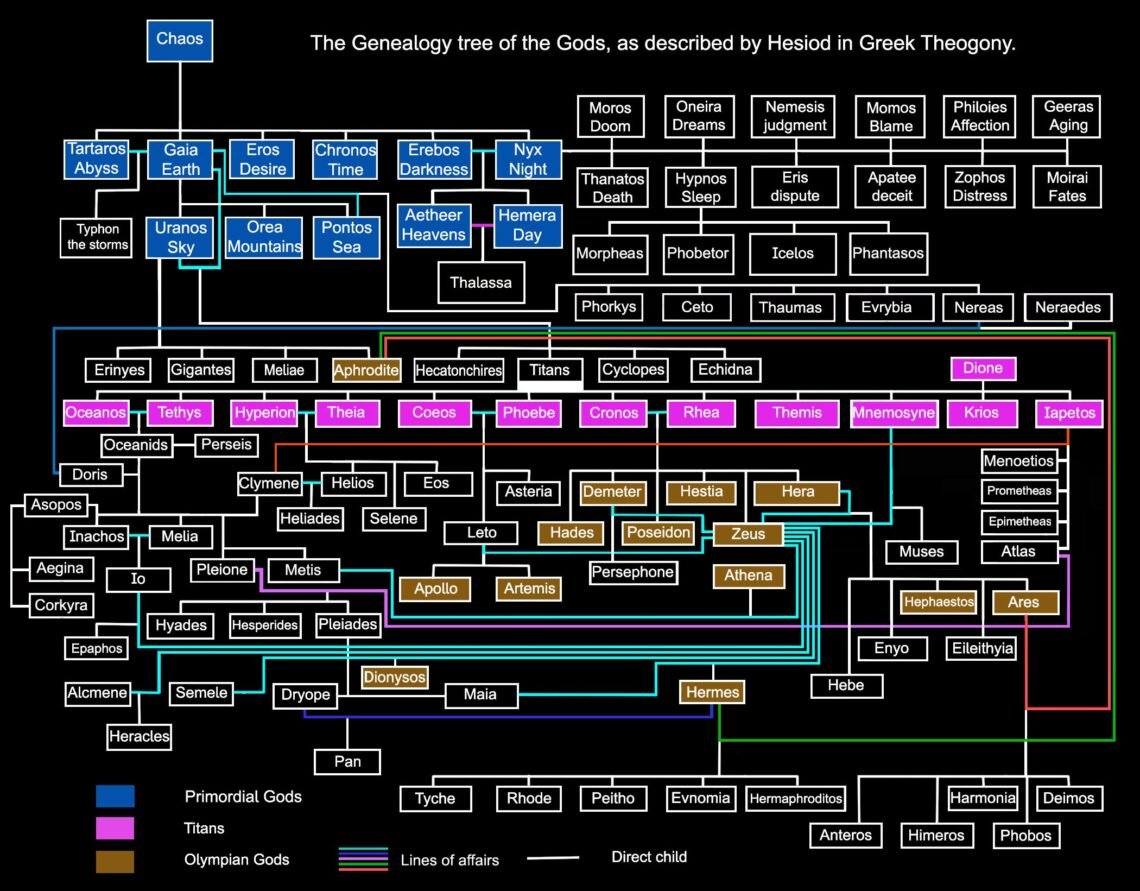

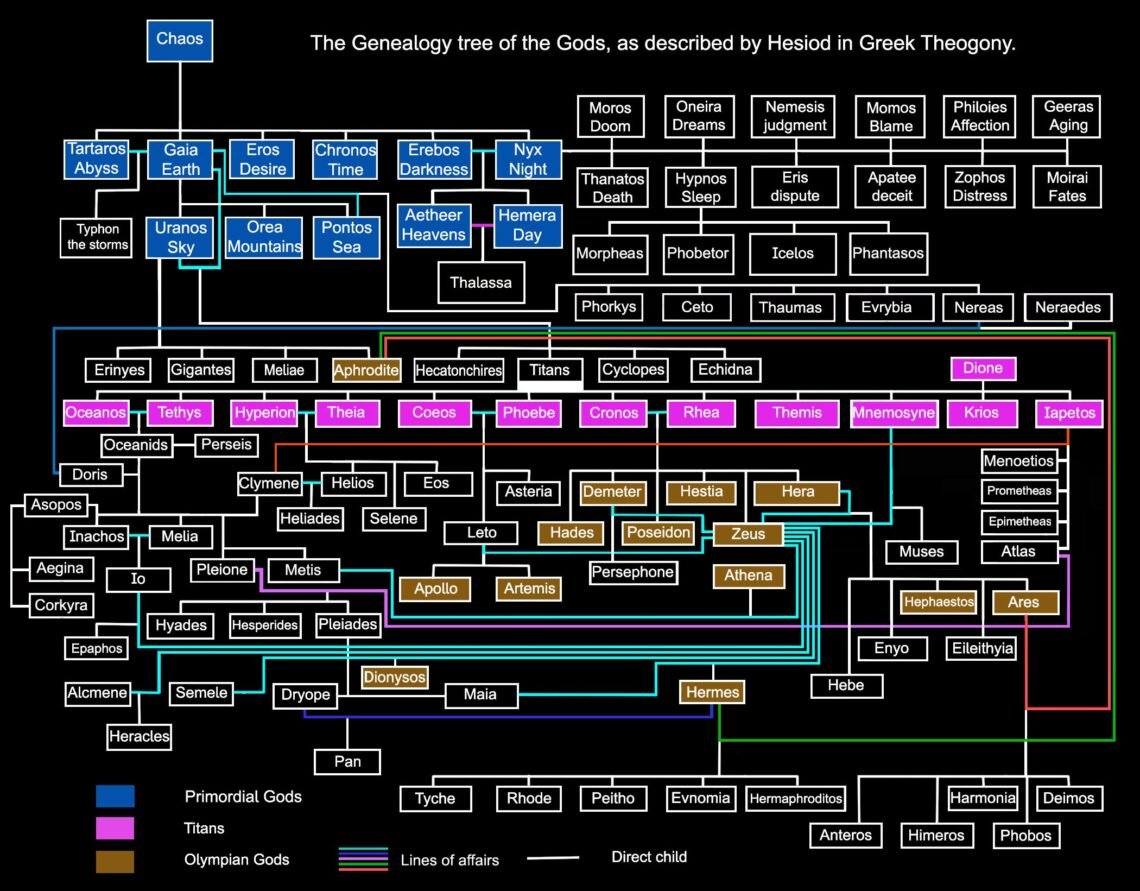

Titan’s and God’s family tree

As per Hesiod’s “Theogony,” the divine hierarchy unfurled across three distinct epochs: the Primordial Gods, the Titans, and the Olympians.

Theogony in Greek Mythology

We, the Hellenes, possess our very own Theogony – often referred to as Cosmogony due to its intricate exploration of the birth of the Kosmos (Greek for Cosmos, the Universe). This significant facet is an integral part of Hellenic (Greek) mythology.

Each ancient religion boasts its unique Theogony. The Greek Theogony, an epic poem of over a thousand lyrical lines, was penned by the illustrious Hesiodos (Hesiod). Bursting with captivating narratives, it chronicles the epic battles between Gods and Titans, many of which are imbued with a charming and somewhat innocent quality.

These stories have been passed down through generations, evolving in the retelling. They delve into the inception of the Universe (also known as the Cosmos, hence it’s referred to as Cosmogony) and predominantly center around the birth (Genesis in Greek) of Titans and Gods.

Hesiod, much like the legendary Homer, was an epic poet of great renown. He undertook the remarkable feat of compiling these narratives and weaving them into the fabric of the Theogony around 700 BCE – a substantial period after Homer’s composition of the Iliad and Odyssey around 762 BCE, and long after the conclusion of the Trojan War.

In his endeavor, Hesiod endeavored to corral the diverse myths circulating throughout Greece regarding the world’s creation and the emergence of the Gods. Furthermore, he ventured to untangle the intricate genealogical web of the Gods woven by these myths.

Theogony, Cosmogony, or Genesis

The Greek word “Theogonia,” which is “Theogony,” stems from the fusion of “Theos,” meaning God, and “Gonos,” meaning offspring, derived from the verb “Gennao,” signifying “I give birth.” Therefore, its literal translation is “the birth of Gods.” (Θεών Γέννεσις in Greek)

On the other hand, “Cosmogonia,” corresponding to “Cosmogony,” emerges from “Cosmos,” denoting the Universe, and “Gonos.” This amalgamation signifies the birth of the Universe.

Furthermore, there exists the term “Genesis,” signifying birth; in fact its synonymous with Gonos as they both stem from the same root, although its scope encompasses a broader range of births.

So, when deciding between “Theogony,” “Cosmogony,” or “Genesis,” it’s crucial to consider the context. Hesiod’s work focuses on the birth and genealogy of deities, making “Theogony” the most fitting choice.

Order out of Chaos

In the beginning, there was only a solitary element: Chaos, an entity without origin or end, emerged shortly after the colossal event known as the Big Bang. For the ancients, Chaos was not disorder and or destruction, but the absolute calm of nothingness—an endless void.

At a certain juncture, two deities emerged from Chaos in an instant. Chronos, the embodiment of time and space‘s inception, materialized alongside Anangee (need), the embodiment of the primal need for Creation.

Of course, the ancients were unaware of the concept of the Big Bang. To them, the emergence of Chronos (Time) marked the genesis of all existence.

In their pursuit, the Greeks conjured order from Chaos, attributing significance and names to their wondrous creations. Their pantheon of Gods and the tapestry of myths were born from the intricate depths of the human imagination, offering an exploration into the realms of the divine.

In their grand tapestry, they forged Titans, Gods, and a myriad of celestial tales, shaping the very fabric of the Cosmos as we comprehend it today.

Let us now venture into this unfolding narrative, as recounted within “Theogonia.”

The Primordial Gods

Emerging from the primordial chaos, a radiant assembly of seven deities graced existence. Among them, Gaia, the revered Mother Earth, held paramount significance. Eros, the embodiment of desire, shared the stage alongside Tartaros, the original deity of the underworld. Erebos, guardian of darkness, and Nyx, the harbinger of night, completed this celestial assemblage.

Two venerable entities, preexisting the cosmic dawn, were intrinsic to this grand narrative: Chronos, the venerable father time, who initiated the passage of time, and Anangee, the embodiment of destiny and creation, bearing the profound weight of purpose.

These seven, the pioneers of the cosmos, were revered by the early denizens of the Bronze Age.

Gaia, untouched by fertilization, brought forth three more gods: Ouranos, the expansive sky enveloping the earth like an ardent lover; Pontos, the vast sea stretching to infinity; and Orea, the majestic mountains that touched the heavens.

Nyx, ignited by Eros, entwined with Erebos, birthing Etheras and Hemera, the embodiments of day and night.

Gaia and Ouranos, a celestial pair, fostered offspring. From their union arose the Kyclopes, the formidable Heckatoncheires, and the twelve potent Titans.

Gaia, in her maternal scope, had also birthed the Gigantes, enormous beings of great strength, who, like Typhon, would one day clash with the Olympians in the epic Gigantomachy. Even in this early era, the cosmos was alive with tension, as creation and destruction coexisted in delicate balance.

From Tartaros, the lord of the underworld arose a legion of monsters, including Cerberos, the guardian of the abyss, and the fearsome Dragon, guardian of the Golden Fleece, which Jason and the Argonauts sought. The enigmatic Sphinx, with a human face, lion body, and bird wings, also sprang forth.

In this ancient perspective, the underworld lacked the Christian concept of hell, instead representing a shadowy realm where souls lingered eternally without influence over the living.

Pontos, the originator of the sea, yielded notorious creatures: the Harpies, Sirens, and Gorgons. Chief among them was Medusa, her serpent hair capable of petrifying anyone who dared gaze upon her.

Descendants of Pontos included the Graies, three crones who shared a tooth and an eye, foreseeing fate. Their name, even in modern Greek, signifies old women—a timeless echo from the Bronze Age.

In the seas, more children of Pontus continued to flourish. Nereus and his daughters, the Nereids, an enchanting cohort of female sea nymphs, wandered the oceans, while creatures like Phorcys, Ceto, and the Graiae shaped the myths that would confound heroes for generations. Among them, Scylla and Charybdis would become names of caution for sailors, their legends echoing in every nautical tale.

Erebos and Nyx engendered an array of primordial figures. Charon, the ferryman of the underworld, is featured among them.

Nyx also spawned a host of entities personifying human fears and notions: Moros (Doom), Thanatos (Death), Oneira (Dreams), Nemesis (Divine Judgment), Momos (Blame), Phillies (Affection), Geeras (Aging), Eris (Dispute), Apatee (Deceit), Zophos (Distress), Moirae (Fates), and Hypnos (Sleep).

Hypnos fathered Phorkys, Phobetor (the scarecrow), Ikelos, and Phantasos (Phantasy). These myriad deities, woven into the tapestry of time, speak of the grandeur and complexity of early mythology.

Monsters born

From Gaia’s boundless womb, not only Titans and cyclopes arose, but also a darker, more fearsome lineage.

Among them was Typhon, a monstrous storm-giant of terrifying might, whose hundred serpentine heads reached the heavens, and Echidna, half-woman, half-serpent, who became the mother of countless fearsome beasts: the Chimera, the Nemean Lion, the Hydra of Lerna, and Orthrus, the two-headed hound.

Together, these two were the architects of much of the chaos that would later challenge gods and mortals alike.

The Titans

The Titans, the second generation of Gods, emerged from the union of Gaia and Ouranos, numbering a formidable twelve.

Oceanos, the God of the ocean, and Tethys, the river goddess, assume positions instead of Pontus within this epoch. Their union birthed the Okeanides, a vast congregation of sea goddesses whose significance would unfold in the tales to come.

Hyperion, God of light, and Theia, Goddess of the ether, brought forth Helios, the original Sun God, and Selene, the first goddess of the moon.

Koeos, in consort with Phoebe, bestowed upon the world Asteria (group of stars), Leto, and the formidable Olympian twins, Artemis and Apollon.

While some of the twelve Titans formed couples, others remained solitary. Krios, not aligned with a consort among the Titans, wed a daughter of Pontus. Their union begots Pallas, the original God of War.

Pallas united with Sphynx, their offspring numbering four: Kratos (translated to Strength in modern times), Nike, the Goddess of Victory, Zelea, the embodiment of Jealousy, and Via, the deity of Violence and Force.

Kronos, God of the harvest, and Rhea, goddess of fertility, assume the mantle of paramount significance within this generation, for they birthed pivotal Olympians, including Dias (Zeus).

Themis, Mnemosyne, Dione, and Iapetos complete the roster of the last four Titans.

Of them, Iapetos emerges as a central figure, fathering Atlas, the deity famed for supporting the world on his shoulders. Additionally, Iapetos sired Prometheas and Epimetheas, Gods embodying foresight and hindsight.

Prometheus, the harbinger of humanity and bearer of fire, stands as a significant offspring, while Epimetheus wed the inaugural woman, Pandora.

Returning to Kronos and Rhea, they reign as the king and queen of this Titan generation. While Ouranos and Gaia initially held the throne, the myth suggests Kronos and Rhea’s ascent due to the following course of events.

Ouranos, harboring disdain for his progeny with Gaia, notably the Hecatoncheires with their hundred hands, cast them deep into the recesses of Earth. Gaia, nursing both sorrow and ire, forged a colossal sickle and implored the Titans to sever Ouranos‘ reign.

Cronos, the youngest of the Titans, undertook the audacious feat, effectively castrating his father. From the spilled blood emerged the Furies, the vengeful goddesses, as well as the Meliae nymphs and an assembly of Giants and Erinyes.

Some renditions even assert the birth of the Goddess of love, Aphrodite, born from the sea foam encircling Ouranos’ discarded genitals near the shores of Cyprus.

Consequently, Cronos and Rhea ascended as the new rulers of the divine realm.

However, history repeated as Cronos banished the Hecatoncheires, a continuation of his father’s decree. This fateful choice beckoned a prophecy: just as Cronos vanquished his progenitor, a child of his would one day dethrone him.

Fearing this outcome, Cronos devoured each of his offspring upon birth. Six children graced the union of Cronos and Rhea, destined to constitute the third and final generation of Gods, the Olympians.

Though Cronos consumed the first five, a cunning stratagem transpired upon the birth of the sixth child, Dias. Rhea tricked Cronos, wrapping a stone as a decoy. Ingesting the rock, believing it to be Zeus, Cronos unwittingly spared the true child.

Safeguarded by Rhea, Zeus matured, poised to challenge his father’s dominion.

Meanwhile, the Titans, though mighty, were not all unified. Some, like Iapetos, fathered legendary figures who would shape the human and divine world.

Atlas, condemned to uphold the heavens, and Prometheus, the foreseer and benefactor of humankind, exemplify the blend of divine ambition and mortal consequence.

Prometheus’ brother, Epimetheus, whose hindsight lagged behind his brother’s foresight, took Pandora as his bride, unwittingly unleashing both woes and wonders into the human realm.

The Titanomachy – Clash of the Titans

Dias, or Zeus, matured under the nurturing care of Nymphs who cradled the newborn, nourishing him with the milk of a goat named Amalthea.

In time, he acquired the strength to challenge his father, Kronos. With a resolute determination, Zeus sundered Kronos’ stomach, liberating his captive siblings and ushering forth the Hecatoncheires, who joined him as steadfast allies in the impending war against the Titans.

Another rendition presents a different course, wherein Zeus employed a potent elixir to compel Kronos to disgorge his offspring. Unbeknownst to Kronos, his divine progeny remained alive within his belly due to their inherent immortality.

Zeus united a formidable assembly of deities, comprised of his siblings and children, alongside the venerable Aphrodite.

During the climactic Titanomachy, certain Titans rallied to the side of the Gods. Notably, Aphrodite, a Titaness, joined the celestial fray, alongside three brothers—Prometheus, Epimetheus, and Atlas—sons of Iapetos. Additionally, the Titaness Mnemosyne transitioned from Titan to Zeus’ mistress.

Led by Zeus, the Gods emerged victorious, relegating the vanquished Titans to Tartara (known as Tartarus in Roman myth), a bleak, distant realm detached from Earth. The Hecatoncheires assumed the role of their custodians in this shadowed domain.

This epochal struggle, often referred to as the Clash of the Titans, culminated in the prophesied outcome—Zeus‘ triumphant defeat of Kronos. This victory propelled Zeus to ascend as the third and ultimate sovereign among the pantheon of Gods.

The 12 Olympian Gods

The initial quintet of Rhea’s liberated children comprised Poseidon, Demetra, Hera, Hades (also known as Plouton, the new deity of the underworld), and Hestia.

Poseidon, uniting with a Nereid, ascended as the novel God of the sea. Demetra assumed Kronos’ former mantle, reigning as the goddess of the harvest.

Dias, the omnipotent king of the Gods, claimed dominion over the sky, specifically embodying the realm of thunder. Alongside his siblings, he established his sovereign seat atop Mount Olympus, from whence he governed the cosmos.

In a divine union, Dias wed his sister Hera, who ascended as the regal queen of the Gods, as well as the matron deity of women.

Hades, or Plouton, took up the mantle of the God presiding over the underworld, while Hestia was consecrated as the goddess of the hearth.

The name of the dwarf planet Pluto draws from the Greek deity of the underworld (though employing the Roman name), rather than Mickey Mouse’s faithful canine companion.

Source from Wikipedia: The name Pluto, after the Greek/Roman god of the underworld, was proposed by Venetia Burney (1918–2009), an eleven-year-old schoolgirl in Oxford, England, who was interested in classical mythology. She suggested it in a conversation with her grandfather, Falconer Madan, a former librarian at the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Library, who passed the name to astronomy professor Herbert Hall Turner, who cabled it to colleagues in the United States.

Each member of the Lowell Observatory was allowed to vote on a short list of three potential names: Minerva (which was already the name for an asteroid), Cronus (which had lost reputation through being proposed by the unpopular astronomer Thomas Jefferson Jackson See), and Pluto. Pluto received a unanimous vote.

The name was published on May 1, 1930. Upon the announcement, Madan gave Venetia £5 (equivalent to £336 in 2021, or US$394 in 2021) as a reward.

And further down, we read: The name ‘Pluto’ was soon embraced by the wider culture. In 1930, Walt Disney was apparently inspired by it when he introduced Mickey Mouse and a canine companion named Pluto, although Disney animator Ben Sharpsteen could not confirm why the name was given.

Athena, the Goddess of wisdom, bestowed her name upon the city of Athens. She emerged as the offspring of Dias and his first wife, Metis, an Oceanid.

Dias and Hera brought forth Hephaestos, the fiery God, and Ares, the embodiment of war.

Hermes, the fleet-footed messenger of the Gods, sprang from Dias and Maia, a daughter of Atlas. His iconic winged helmet distinguishes him as a bridge between earthly and celestial realms, embodying diverse roles.

Dionysos, born from Dias’ dalliance with Semele, an Oceanic nymph, reigned as the God of revelry and wine.

Completing this divine lineage, Apollon, the radiant God of the sun, and Artemis, the silvery Goddess of the moon, hailed from Leto. She was another of Dias’ myriad mistresses, the daughter of Titans Koios and Phoebe.

Apollon also assumed dominion over medicine and the arts, while Artemis stood as the Goddess of hunting.

Thus, the Olympian pantheon encompasses the five siblings of Dias, coupled with seven offspring from Hera and various unions, plus Aphrodite. It’s worth noting that, in an alternative myth, Aphrodite was Dias’ daughter, distinct from the sea foam-born deity mentioned earlier.

With 14 Gods in the roster instead of the anticipated 12, Hesiod skillfully resolves this incongruity. Hestia, for one, ceded her Olympian seat to Dionysos, while Hephaestos primarily resided in his workshop in Lemnos island.

Minor deities

Yet, the tapestry of the Theogony continues, unfolding countless siblings, minor deities, and demigods. Dias, who strayed from fidelity to Hera, fathered a diverse array of progeny.

From his union with Titaness Mnemosyne, the Nine Muses, sources of music and art, were born.

Dias sired Epaphos through Io, and with Hera, brought forth Hebe, Enyo, and Eileithyia. The mightiest hero of all, Heracles, traced his lineage to Dias and his affair with Oceanid Alcmene.

Notably, other Gods also fathered children. Aris, the God of war, shared an enduring liaison with Aphrodite, birthing Harmonia, Anteros, Himeros, Deimos, and Phobos, the latter two correlating with the moons of Aris (Mars in Roman mythology).

Hermes and Aphrodite brought forth five children: Tyche (Luck), Rhode, Peitho (Persuasion), Evnomia, and Hermaphroditos, a being embodying both sexes.

The Gigantomachy

However, the Gods encountered another formidable trial in the form of the Giants, the offspring of Ouranos.

Consequently, a fresh conflict arose: the Gigantomachy, a battle as protracted as its predecessor.

Ultimately, the Gods emerged victorious, vanquishing the Giants and establishing their majestic abode atop Mount Olympus in Thessaly. From this celestial citadel, they wielded dominion over the realms of existence.

Planets named after the gods of Greek mythology

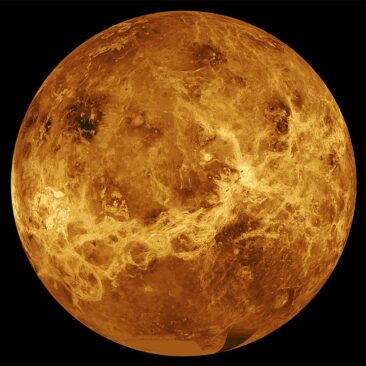

Presenting a collection of planetary photographs, each adorned with its original Greek appellations, honoring the legacy of the Gods.

This stance firmly opposes the Roman adaptations, which have, in essence, misshaped their identities.

Indeed, the Roman pantheon stands as an assortment of pilfered imitations, far from the genuine counterparts venerated in ancient Greece.

This discrepancy is often fueled by Western historians’ lack of historical accuracy.

By embracing the Greek nomenclature, a distinct linguistic divergence emerges.

An ‘O‘ supersedes the Latin ‘U,’ ‘K‘ substitutes ‘C,’ and a trailing ‘N‘ frequently finds its place—thus, Apollon supplants Apollo, and Pluton outshines Pluto.

It’s worth noting that the original epithet for the lord of the underworld is Hades.

Conclusion

As the visuals unfold before you, it becomes evident that the ancient Greek Gods were no more than embodiments of the very passions, fears, and emotions that continue to wield influence over our lives even in our present era.

A discernible pattern emerges, wherein human passions, particularly the trepidations inherent to human nature, take center stage in the grand narrative of Theogony.

The pantheon is replete with deities embodying our fears and anxieties, encapsulating the profound gamut of human sentiments—evidenced by the very essence of their appellations.

Ancient Greek religion stands worlds apart from contemporary faiths. Greek Mythology, the bedrock of their belief system, contrasts starkly with the doctrines of today.

Instead of dogmas and vengeful deities, it epitomizes a melodic celebration of human emotions, fearlessly charting the depths of our innermost feelings. It can best be characterized as a philosophical tapestry rather than a conventional religion.

In our modern era, it seems the ancient Greek deities have taken a vacation from the faith department. But don’t be fooled, they’ve got some serious staying power in the storytelling arena, like those favorite old jeans you can’t part with.

Yep, these divine tales are the ultimate time travelers, strutting through history like they own the place. They’re like the cool grandpas of myths, refusing to retire to the dusty attic of forgotten tales.

And let’s not forget, their enchantment game is still going strong. It’s like they’ve got an eternal Netflix subscription to captivate our imaginations. These stories are the fountain of creativity, bubbling with ideas for writers, artists, and daydreamers alike.

Oh, but hold onto your popcorn, because here’s the kicker: What about a Hollywood blockbuster of epic proportions? Zeus, the ultimate Casanova, swept across the silver screen with more charm than a horde of heart-eye emojis. No mortal or goddess left unsatisfied – talk about divine intervention!

So, my friends, brace yourselves for a cinematic extravaganza that would make even the Gods themselves give a standing ovation. It’s a vision so gripping that even Mount Olympus would be quaking with excitement.

Comments