The pantheon of Greek gods and mythical beings, spanning generations of divine and semi-divine figures, stands as a testament to the timeless power of storytelling.

Greek mythology not only shaped the culture and beliefs of ancient Greece but also left an enduring legacy on the cultural heritage of humanity, influencing literature, art, and worldviews across centuries.

Greek mythology is a rich tapestry of divine beings and stories, with each generation of gods possessing its own unique qualities, roles, and rulers.

These generations of gods are integral to the mythological narrative and offer insights into the evolving beliefs and values of ancient Greece.

Here is an in-depth exploration of the main generations of Greek gods:

Primordial Deities

At the dawn of creation, the universe was shaped by primordial forces—divine entities representing fundamental aspects of reality rather than anthropomorphic gods. These early beings, including Chaos, Chronos (Time), and Ananke (Necessity), embodied the essential principles of existence: the void, the passage of time, and the inevitability of fate.

Primordials were less human-like and more abstract, personifying natural elements and cosmic forces. Over successive generations, many of these formless entities gradually took on more human-like shapes, laying the foundation for the Titans and Olympians.

Some of the main primordial entities include:

- Chaos – The formless void, the origin of everything.

- Chronos (Time) – The force of temporal progression, ordering the cosmos. (Not to be confused with Cronus, the Titan leader; Chronos is a primordial force existing alongside Chaos and Ananke.)

- Ananke (Necessity) – The force of inevitability, compulsion, and cosmic law.

- Gaia (Earth) – Personification of the Earth itself.

- Tartarus – The abyss, serving as a prison for cosmic threats.

- Eros – The force of procreation and attraction.

- Erebus – The darkness of shadow and the void.

- Nyx – The night and all its mysteries.

From those deities more emerged, such as:

- Uranus (Ouranos): The personification of the sky or heavens. He is a fundamental primordial deity, the son and husband of Gaia, and the father of the Titans.

- Orea: Orea, also known as Ore, is a lesser-known primordial goddess who personifies mountains and mountain ranges. She is a representation of the ancient and enduring nature of the Earth’s geological formations.

- Pontos: Pontos is the personification of the sea, often regarded as the deep, abyssal waters. He is the son of Gaia and, in some accounts, represents the vast expanse of the sea before it was organized into the domains of other sea deities.

- Moros: Moros is the personification of impending doom or fate. He represents the inexorable and inescapable fate that awaits all beings in the universe. Moros is associated with the concept of mortality.

- Oneiroi (Oneira): The Oneiroi are a group of primordial deities who personify dreams. They are the children of Nyx and represent the various types of dreams, including prophetic, surreal, and nightmare-inducing dreams.

- Nemesis: Nemesis is the personification of divine retribution and vengeance. She ensures that those who display hubris or excessive pride are punished and that justice is served.

- Momos: Momos is the personification of satire, mockery, and criticism. He represents the critical and humorous aspect of art and literature, highlighting the flaws and absurdities of others.

- Philies: Philies is the personification of affection and love between individuals. She represents the positive and affectionate connections that form between people.

- Geras: Geras is the personification of old age. He symbolizes the inevitable aging process and the physical and mental challenges that come with it.

- Thanatos: Thanatos is the personification of death. He represents the peaceful or gentle death that allows individuals to pass away without suffering.

- Hypnos: Hypnos is the personification of sleep. He is often depicted with his twin brother, Thanatos, and together they represent the peaceful transition from life to death.

- Eris: Eris is the personification of strife and discord. She is known for her role in causing the Trojan War by throwing the golden apple of discord, which led to a conflict among the goddesses.

- Apate: Apate is the personification of deceit and deception. She represents the art of cunning persuasion and manipulation.

- Zophos: Zophos is a lesser-known primordial deity who personifies darkness or gloom. While not as prominent as Erebus, Zophos is associated with shadowy or dimly lit places.

These primordial deities and personifications are integral to Greek mythology and offer insights into the ancient Greeks’ understanding of the fundamental aspects of the universe, from natural forces to abstract concepts like fate and dreams. Each one played a unique role in shaping the Greek mythological landscape and contributed to the rich tapestry of stories and beliefs in ancient Greece.

Titans

The Titans were a powerful and ancient race of deities in Greek mythology. Building on the cosmos shaped by the primordial forces, the Titans inherited and personified many aspects of the universe in more tangible forms. They were the immediate predecessors of the Olympian gods and played a significant role in the cosmogony and early history of the Greek pantheon.

Here are the most well-known Titans:

- Cronus (Kronos): The leader of the Titans and the youngest son of Uranus (Sky) and Gaia (Earth). Cronus overthrew his father Uranus and later ruled as the king of the Titans. He is often associated with time and was notorious for swallowing his children to prevent them from usurping his power. His most famous child to survive this fate was Zeus, who eventually overthrew Cronus and the Titans.

- Rhea: The Titaness Rhea was the sister and wife of Cronus. She was the mother of several major gods, including Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Hades, Demeter, and Hestia. Rhea is often associated with fertility and motherhood.

- Oceanus: Oceanus was the Titan of the world ocean, believed to encircle the Earth. He was married to the Titaness Tethys, and together they were the parents of the Oceanids, nymphs associated with various bodies of water.

- Hyperion: Hyperion was the Titan of heavenly light, often associated with the sun. He and his sister Theia were the parents of several important deities, including Helios (the sun), Selene (the moon), and Eos (the dawn).

- Mnemosyne: Mnemosyne was the Titaness of memory and the mother of the Muses, nine goddesses who presided over the arts and sciences. Mnemosyne played a crucial role in inspiring creativity and preserving knowledge.

- Themis: Themis was the Titaness of divine law and order. She represented the principles of justice, fairness, and custom. Themis was also known for her prophetic abilities.

- Coeus (Koios): Coeus was the Titan of intellect and the inquiring mind. He was married to his sister Phoebe and was considered one of the Titans associated with cosmic knowledge.

- Phoebe: Phoebe was the Titaness of the moon and the intellect. She and Coeus were the parents of Leto, who in turn was the mother of Apollo and Artemis.

- Crios (Krios): Crios was the Titan of constellations and the measurement of time. He and his sister Eurybia were the parents of Astraeus, Pallas, and Perses.

- Eurybia: Eurybia was a Titaness of the mastery of the seas. She was married to Crios and was the mother of Astraeus, Pallas, and Perses.

- Prometheus: Prometheus was a Titan known for creating humanity out of clay and for stealing fire from the gods to benefit humankind. He played a significant role in several myths and was known for his cleverness and defiance.

- Epimetheus: Epimetheus, whose name means “afterthought,” was Prometheus’ brother. He was responsible for giving animals their various attributes and characteristics.

These are some of the most prominent Titans in Greek mythology, but there were others as well, each associated with various aspects of the natural world and cosmic order.

The Titans’ conflict with the Olympian gods, known as the Titanomachy, marked a pivotal moment in Greek mythology and cosmology, leading to the establishment of the Olympian pantheon as the dominant force in the Greek divine hierarchy.

Olympian Gods

The Olympian gods represent perhaps the most iconic and well-known generation of deities in Greek mythology.

Unlike the formless forces of the Primordials or the elder Titans, the Olympians were more anthropomorphic, embodying human traits alongside their divine powers.

The Olympian gods not only dominated myth and legend but also marked the culmination of the Ancient Greek religious system, representing the fully developed pantheon that shaped Greek worship, ritual, and cultural identity for centuries.

They were the divine rulers of Mount Olympus, a majestic peak in Greece, and their stories, attributes, and interactions with mortals have left an indelible mark on Western culture and literature.

Led by the mighty Zeus, these gods supplanted the Titans, ushering in a new era of divine governance. Here is an expanded look at some of the key Olympian gods:

- Zeus (Jupiter): Zeus, the king of the gods, wielded thunderbolts as his symbol of power. He was the ruler of the sky and the heavens, responsible for maintaining order and justice in the cosmos. Zeus was also associated with hospitality, law, and the protection of guests.

- Hera (Juno): As the queen of the gods and Zeus’s wife, Hera presided over marriage and childbirth. She was known for her jealousy and her role in the lives of mortal women, especially those who had affairs with her husband.

- Poseidon (Neptune): Poseidon was the god of the sea, earthquakes, and horses. He was a tempestuous deity who could cause storms or calm the waters, depending on his mood. His trident was his iconic weapon.

- Demeter (Ceres): Demeter was the goddess of agriculture and the harvest. She controlled the fertility of the earth, and her grief over the abduction of her daughter Persephone led to the changing seasons.

- Hestia (Vesta): Hestia was the goddess of the hearth and home. She symbolized domesticity, hospitality, and the sacred fire that burned in every Greek household.

- Ares (Mars): Ares was the god of war and violence. He represented the brutal and chaotic aspects of battle, in contrast to Athena, who symbolized strategic warfare.

- Athena (Minerva): Athena was the goddess of wisdom, courage, and warfare. She was a patron of heroes and the city of Athens, and her symbol was the owl.

- Apollo: Apollo was a multifaceted god associated with the sun, music, prophecy, healing, and archery. He was often depicted as the ideal of youthful beauty and artistic inspiration.

- Artemis (Diana): Artemis was Apollo’s twin sister and the goddess of the hunt, wilderness, and the moon. She was a skilled archer and protector of young girls.

- Aphrodite (Venus): Aphrodite was the goddess of love, beauty, and desire. Her birth from the sea foam and her irresistible allure made her a central figure in myths involving love and attraction.

- Hephaestus (Vulcan): Hephaestus was the god of blacksmiths, craftsmen, and fire. Despite his physical deformity, he was a master of metallurgy and created powerful weapons and exquisite art.

- Hermes (Mercury): Hermes was the messenger god, known for his swiftness and cunning. He was the patron of travelers, merchants, thieves, and diplomacy.

- Dionysus (Bacchus): Dionysus was the god of wine, fertility, and revelry. He was associated with both the joys and excesses of life, representing the dual nature of ecstasy and madness.

The Olympian gods played central roles in Greek mythology, and their complex personalities and interactions with both mortals and one another gave rise to a multitude of captivating stories.

These tales explored themes of power, love, jealousy, justice, and the enduring connection between the divine and human worlds.

Heroes and Demigods

Heroes and demigods were extraordinary figures in Greek mythology, straddling the line between mortal and divine, and often undertaking epic quests and adventures.

These individuals, born of both human and divine parentage or endowed with exceptional qualities, captured the imaginations of ancient Greeks and continue to be celebrated in literature and culture.

Here’s an expanded look at some of these legendary heroes and demigods:

- Heracles (Hercules): Heracles, the most famous of all Greek heroes, was the son of Zeus and Alcmene. He possessed unmatched strength and courage and was known for his Twelve Labors, a series of incredible tasks that included slaying the Nemean Lion, capturing the Erymanthian Boar, and cleaning the Augean Stables. Heracles’ legendary exploits became the embodiment of heroism, and he was revered as a symbol of strength, endurance, and resilience.

- Perseus: Perseus, the son of Zeus and Danaë, was renowned for his quest to slay the Gorgon Medusa and rescue Andromeda from a sea monster. He was aided by divine gifts, including a reflective shield from Athena, winged sandals from Hermes, and a cap of invisibility from Hades. Perseus’ adventures showcased resourcefulness and cunning, making him a hero celebrated for his wits and bravery.

- Achilles: Achilles, the son of Peleus (a mortal) and Thetis (a sea nymph), was a Greek hero of the Trojan War. He was known for his invulnerability, except for his heel, which became his fatal weakness. Achilles’ tragic story and extraordinary combat skills, as depicted in Homer’s “Iliad,” have made him an enduring symbol of valor and the human condition.

- Theseus: Theseus, the son of Aegeus (king of Athens) and either Aethra or Poseidon, is remembered for his slaying of the Minotaur in the Labyrinth of Crete. He navigated a maze, defeated the monstrous Minotaur, and found his way back to Athens using a thread given to him by Ariadne. Theseus’ heroic feats, which included ridding the road to Athens of bandits and becoming a champion of justice, established him as a national hero and symbol of Athenian identity.

- Bellerophon: Bellerophon was a Corinthian hero known for taming and riding the winged horse Pegasus. He also undertook quests, including slaying the Chimera, a fire-breathing monster. Bellerophon’s story reflects the theme of human ambition and the pursuit of impossible goals.

- Jason: Jason, the leader of the Argonauts, embarked on a perilous journey to obtain the Golden Fleece. Alongside his crew of heroes, including Heracles and Orpheus, he faced numerous challenges, including encounters with harpies, sirens, and giants. Jason’s heroic voyage is a classic tale of adventure, exploration, and the quest for glory.

These heroes and demigods exemplify various facets of heroism, from strength and cunning to courage and resourcefulness.

Their stories not only entertained ancient Greeks but also conveyed moral lessons and ideals of valor, justice, and the enduring human spirit.

The legacy of these legendary figures continues to inspire and resonate with audiences around the world today.

Chthonic Deities

The Chthonic deities, also known as the “Underworld deities” or “Subterranean deities,” held a unique and essential place within Greek mythology. They were closely connected with the hidden realms beneath the Earth’s surface, including the vast and mysterious domain of the Underworld. Here’s an expanded look at some of the prominent Chthonic deities:

- Hades (Pluton): Hades was the god of the Underworld and the ruler of the realm of the dead. He was one of the three principal Olympian brothers, alongside Zeus and Poseidon. His realm, also known as Hades, served as the final destination for the souls of the deceased, where they underwent judgment and eternal existence. Hades was often depicted as stern and unyielding, but he was not considered malevolent. He was responsible for maintaining order in the Underworld and ensuring that the souls of the dead received their just rewards or punishments. The myth of Hades’s abduction of Persephone played a central role in his story, as it led to her becoming his queen in the Underworld.

- Persephone (Proserpina in Roman): Persephone was the daughter of Zeus and Demeter, the goddess of agriculture. She was known for her beauty and her association with spring and the harvest. Her most famous myth is the abduction by Hades, which led to her becoming queen of the Underworld. Her annual return to the surface brought about the changing seasons, with her descent symbolizing winter and her ascent representing spring’s arrival. Persephone’s story embodies themes of transformation, cycles of life and death, and the enduring bond between the surface world and the Underworld.

- Hecate: Hecate was a goddess associated with crossroads, magic, and the night. She had a complex role in Greek mythology, serving as a guardian of the threshold between the mortal world and the Underworld. Often depicted holding torches, she guided souls along their path in the afterlife. She was also invoked in magical rituals and as a protector of travelers. Hecate was often portrayed as a triple goddess, representing the stages of a woman’s life: maiden, mother, and crone. Her symbolism reflected her multifaceted role in the realms of magic, divination, and the spirit world.

Chthonic deities like Hades, Persephone, and Hecate were crucial to the Greek understanding of life, death, and the mysterious forces that govern the unseen aspects of existence.

They added depth and complexity to the Greek pantheon, demonstrating the interconnectedness of the mortal world and the realms beyond, and providing a framework for exploring themes of mortality, rebirth, and the inexorable passage of time.

Minor Deities

Within the pantheon of Greek mythology, the Minor Gods occupy a diverse and extensive category that enriches the tapestry of the ancient Greek world.

These minor deities, spirits, and mythological creatures played vital, albeit more specialized, roles in the lives of both gods and mortals.

Here’s an expanded look at some of these fascinating minor gods and beings:

Nymphs

Nymphs were ethereal female spirits associated with various aspects of the natural world. They were typically linked to specific locations, such as forests, rivers, mountains, and springs.

- Naiads: Nymphs of freshwater, residing in rivers, streams, and fountains. The most famous is the Echo, which could only repeat what others said.

- Dryads: Nymphs of trees and forests, each inhabiting a particular tree. They were closely connected to the well-being of the trees they inhabited.

- Oreads: Nymphs of the mountains, often depicted as athletic and independent spirits.

- Nereids: Sea nymphs, daughters of Nereus, who accompanied Poseidon and were associated with the Mediterranean Sea.

- Oceanids: Nymphs of the ocean, daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, often representing various aspects of the sea.

River Gods

Each major river in Greece had its river god, known as Potamoi. These deities personified the rivers and were often seen as protectors of their domains.

- Achelous: The river god of the largest river in Greece, often portrayed with the ability to change shape.

- Scamander: The river god of the river near Troy, mentioned in the “Iliad.”

- Peneus: The river god of the Peneus River in Thessaly.

Muses

The Muses were a group of nine goddesses in Greek mythology who personified and presided over the realms of inspiration, creativity, and intellectual pursuits.

These divine sisters were the patrons of various artistic and intellectual endeavors, each overseeing a specific domain. Their influence extended far and wide, inspiring mortals to excel in their chosen fields and contribute to the flourishing of Greek culture.

Here is an expanded look at some of the Muses and their respective domains:

- Calliope (Epic Poetry): Calliope was the Muse of epic poetry and eloquence. She was often depicted holding a writing tablet or a scroll, symbolizing the recording of great heroic tales. Poets and bards invoked Calliope’s guidance when embarking on the composition of epic poems. Her inspiration was sought for works like Homer’s “Iliad” and “Odyssey.”

- Clio (History): Clio was the Muse of history and historical writing. She held a scroll or a book and was responsible for inspiring historians and chroniclers to document the events of the past. Her influence encouraged the recording of historical accounts, ensuring that the deeds of great leaders and civilizations were preserved for future generations.

- Terpsichore (Dance): Terpsichore was the Muse of dance and choral singing. She was often depicted holding a lyre, which represented the music and rhythm that accompanied dance. Dancers, choreographers, and musicians invoked Terpsichore’s blessings to create and perform graceful and harmonious dances and musical compositions.

- Erato (Lyric Poetry): Erato was the Muse of lyric poetry and love poetry. She was often depicted holding a lyre, symbolizing the intimate connection between music and poetry. Poets and writers turned to Erato for inspiration when crafting verses that expressed love, desire, and the emotions of the heart.

- Thalia (Comedy and Idyllic Poetry): Thalia was the Muse of comedy, idyllic poetry, and pastoral arts. She held a comic mask, symbolizing her association with theatrical comedy. Playwrights, poets, and performers sought Thalia’s influence to create lighthearted and humorous works, including comedic plays and poems.

- Melpomene (Tragedy): Melpomene was the Muse of tragedy. She held a tragic mask and a club, signifying the serious and often somber nature of tragic drama. Playwrights and dramatists invoked Melpomene’s inspiration to craft emotionally charged and thought-provoking tragedies that explored profound themes.

- Polyhymnia (Sacred Poetry and Hymns): Polyhymnia was the Muse of sacred poetry, hymns, and eloquence. She was often portrayed in a contemplative pose, meditating on divine and sacred matters. Priests, hymnists, and religious poets called upon Polyhymnia when composing hymns and sacred verses for religious ceremonies and rituals.

- Euterpe (Music and Lyric Poetry): Euterpe is the Muse of music and lyric poetry. She is often shown with a flute, a symbol of her connection to music and the arts.

- Urania (Astronomy): Urania is the Muse of astronomy and celestial poetry. She is often shown gazing at the stars and holding a celestial globe or a compass.

These nine Muses collectively represented the diverse facets of artistic and intellectual pursuits in ancient Greece.

Their influence transcended the boundaries of creativity and knowledge, serving as a source of guidance and inspiration for those who sought to excel in their chosen fields, be it poetry, history, dance, or other forms of expression.

The Muses’ enduring legacy continues to remind us of the profound role that inspiration and creativity play in the human experience.

Horae (Seasons) and Moirai (Fates)

In Greek mythology, the Horae and the Moirai were two distinct groups of goddesses who played crucial roles in shaping the course of human life and the order of the cosmos.

Each group had its responsibilities and significance, reflecting the Greeks’ fascination with the passage of time, fate, and the changing of seasons. Here is an expanded exploration of these two groups of goddesses:

The Horae (Seasons)

The Horae, often referred to as the “Hours” in English, were a group of goddesses who personified and regulated the natural seasons and the orderly progression of time. They were typically depicted as graceful and youthful maidens, often with flowers or wreaths in their hair, symbolizing the changing of the seasons. The Horae were divided into three primary categories, each overseeing a different aspect of time and the seasons:

- Eunomia (Order or Lawfulness): Eunomia represented good order and governance. She ensured that the seasons followed a predictable and harmonious pattern, which was essential for agricultural cycles and the well-being of society.

- Dike (Justice): Dike was the embodiment of justice and moral order. Her presence signified the importance of ethical conduct and the consequences of human actions. She maintained balance and fairness in the natural world.

- Eirene (Peace): Eirene personified peace and prosperity. She was associated with the bountiful and peaceful times that followed the successful harvest seasons. Her presence indicated a time of tranquility and plenty.

The Horae were closely connected to agricultural and rural life, as their regulation of the seasons directly affected crop growth, harvests, and the overall well-being of the Greek populace. They represented the cyclical nature of time and the importance of order and harmony in both the natural and human realms.

The Moirai (Fates)

As primordial forces, the Moirai embodied the earliest concepts of destiny and necessity, a theme that resonates through other abstract deities like Ananke.

They were a group of three sisters who held immense power over the destiny and fate of all living beings.

Often depicted as elderly women, stern and unyielding in their determination.

The three primary Moirai were:

- Clotho (The Spinner): Clotho was responsible for spinning the thread of life. She determined the beginning of one’s life and the circumstances of their birth. She was depicted spinning the thread on a spindle.

- Lachesis (The Allotter): Lachesis determines the length and destiny of an individual’s life. She measured the thread spun by Clotho and assigned the events and experiences that would shape a person’s existence.

- Atropos (The Inevitable): Atropos was the cutter of the thread of life. Once Lachesis determined the length of a person’s life, it was Atropos who decided when that life would come to an end. Her shears represented the finality of death.

The Moirai were relentless and impartial in their duties, making them both feared and revered. They symbolized the inevitability of fate and the idea that every living being, including the gods themselves, was subject to the whims of destiny. The Moirai’s presence in Greek mythology underscored the profound philosophical questions surrounding free will, determinism, and the human condition.

In summary, the Horae and the Moirai were integral to Greek mythology, representing the cyclical nature of time, the importance of order, and the inexorable power of fate. Together, they highlighted the complex interplay between human agency and the forces that shape the course of existence.

Personifications

In Greek mythology, a diverse array of deities personified abstract concepts, embodying various aspects of human life and the natural world.

These anthropomorphic representations allowed the ancient Greeks to explore and understand these concepts within the context of their religious and cultural beliefs.

Here is an expanded look at some of these deities who personified abstract concepts:

- Nike (Victory): Nike was the winged goddess of victory, often depicted with wings and carrying a laurel wreath or palm branch. She symbolized the triumphant outcome of conflicts, contests, and battles. Nike played a significant role in Greek art and culture, representing not only military victory but also success in sports and competitions.

- Eris (Strife): Eris was the goddess of strife and discord. She was often depicted as a troublemaker who sowed chaos and rivalry among gods and mortals. Eris famously initiated the Trojan War by indirectly causing the dispute over the golden apple, which ultimately led to the conflict between the Greeks and the Trojans.

- Tyche (Luck): Tyche was the goddess of luck, fortune, and chance. She represented the capricious and unpredictable nature of fate. Tyche was often depicted holding a rudder, symbolizing her influence throughout events. Her worship was particularly popular in Hellenistic times when people sought to invoke her favor in uncertain times.

- Nemesis (Retribution): Nemesis was the goddess of retribution and vengeance. She ensured that mortals received their due rewards or punishments for their actions. Nemesis encouraged virtuous behavior by punishing hubris and arrogance. She was often depicted with a measuring rod and scales, emphasizing the concept of balance and justice.

- Hedone (Pleasure): Hedone was the goddess of pleasure and enjoyment. She represented the pursuit of sensory and emotional gratification. While not as widely known as some other abstract deities, Hedone played a role in the exploration of human desires and the pursuit of happiness.

- Ananke (Necessity): Ananke was the goddess of necessity and inevitability. She personified the concept that certain events and outcomes are inescapable and bound by fate. Ananke’s role highlighted the limitations of mortal free will and the existence of forces beyond human control. Though often discussed among minor or abstract deities, Ananke, like the Moirai, is primordial, embodying the earliest cosmic forces that shaped fate and necessity.

These abstract deities added depth and complexity to the Greek pantheon, allowing the ancient Greeks to explore profound philosophical and moral questions.

They served as reminders of the often unpredictable and uncontrollable aspects of life, encouraging individuals to contemplate the nature of victory, discord, luck, retribution, pleasure, and necessity within the context of their existence.

Through these deities, Greek mythology provided a lens through which people could grapple with the complexities of the human experience and the world around them.

Underworld Judges

In Greek mythology, the Underworld was not just a realm of the dead, but a domain governed by moral order and cosmic necessity, a role reflected in the judges who determined the fates of souls—echoing the primordial influence of Ananke and the Moirai.

In addition to Hades, the god who ruled over the Underworld, there were judges responsible for determining the fates of the souls who entered their domain.

Three prominent judges of the Underworld were Minos, Rhadamanthus, and Aeacus:

- Minos: Minos was the son of Zeus and Europa and was renowned for his wisdom and sense of justice. After his death, he became one of the judges of the dead in the Underworld. He was often depicted wearing a crown and holding a scepter, symbols of his authority as a judge. Souls would come before him to have their deeds in life evaluated. Minos was especially known for his role in determining the punishments of those who committed grave sins, and he played a key part in the afterlife justice system.

- Rhadamanthus: Rhadamanthus was the son of Zeus and Europa, making him a brother of Minos. He was also a respected judge in the Underworld. Like Minos, Rhadamanthus was known for his fair and impartial judgments. He was considered a model of moral integrity and virtue. Souls facing judgment before Rhadamanthus could expect a thorough and just evaluation of their actions during their mortal lives.

- Aeacus: Aeacus was the son of Zeus and Aegina, and he too held the role of a judge in the Underworld alongside Minos and Rhadamanthus. Aeacus was often depicted holding a staff or a scepter, signifying his authority in the realm of the dead. He was known for his diligence in assessing the souls that came before him. He was also credited with helping to establish the laws of Athens and contributing to the development of early legal and judicial systems in Greece.

These three judges of the Underworld played a vital role in the postmortem fate of souls.

They evaluated the deeds and actions of the deceased, determining whether they were deserving of reward in the Elysian Fields or punishment in Tartarus.

This system of judgment reflected the Greek belief in the accountability of individuals for their actions in life and the consequences they would face in the afterlife.

The presence of judges in the Underworld added depth to Greek mythology’s exploration of morality, justice, and the consequences of one’s actions.

It reinforced the idea that ethical conduct and adherence to societal norms were important not only in the mortal realm but also in the realm of the dead, where individuals would ultimately face judgment for their deeds.

Creatures and Monsters

Satyrs and Fauns

Satyrs and fauns are mythical creatures that have their origins in Greek and Roman mythology, respectively.

These half-human, half-goat beings are known for their association with wild and uninhibited behavior, as well as their connection to nature and the god of wine, Dionysus (Bacchus in Roman mythology). Here’s an expanded look at both satyrs and fauns:

Satyrs in Greek Mythology

Satyrs were creatures with the upper body of a human and the lower body of a goat, complete with hooves and a goat’s tail. They possessed goat-like features, such as pointy ears and sometimes horns on their foreheads.

Satyrs were notorious for their hedonistic and mischievous nature. They were often depicted as revelers who enjoyed wine, music, dance, and all forms of merriment. Their wild behavior and unrestrained revelry were a stark contrast to the disciplined and civilized nature of the ancient Greek city-states.

Dionysus, the god of wine and ecstasy, was the patron deity of satyrs. They were considered his loyal followers and often accompanied him in his entourage. Satyrs played musical instruments like panpipes and enjoyed participating in Dionysian festivals, such as the bacchanalia.

In Greek mythology, satyrs were known for their amorous pursuits and were often depicted pursuing nymphs or maenads, female followers of Dionysus.

Fauns in Roman Mythology

Fauns were the Roman equivalent of Greek satyrs and shared many similar characteristics. Like satyrs, they had the upper body of a human and the lower body of a goat.

Fauns were associated with the Roman god Faunus, who had attributes similar to those of Dionysus. Both gods were linked to nature, fertility, and the wilderness. Faunus was considered the god of the forest and the protector of shepherds and farmers.

Similar to satyrs, fauns were known for their love of wine, dance, and revelry. They were often portrayed as carefree and mischievous beings who roamed the woods and rural areas of ancient Italy.

Fauns were believed to have the ability to prophesy and communicate with animals. They were seen as intermediaries between the natural world and humanity.

The most famous faun in Roman mythology is Faunus himself, who was also associated with prophetic dreams and divination. His sanctuary in Rome, the Lupercal, was a place of worship and divination.

Both satyrs and fauns are enduring symbols of the untamed and primal aspects of human nature. They represent the juxtaposition of civilization and wilderness, order and chaos, and the allure of the natural world.

Their connections to wine, music, and revelry reflect the human desire for ecstatic experiences and communion with the divine.

These mythical creatures continue to be intriguing figures in the rich tapestry of Greek and Roman mythology.

Daimones (Spirits, Demons)

Daimones were spirits or divine beings associated with specific aspects of life, natural phenomena, or concepts.

- Eidothea: A sea nymph who helped Menelaus in “The Odyssey.”

- Nemesis: The goddess of retribution and balance ensured that mortals received their due rewards or punishments. Some daimones overlap with other categories.

- Thanatos: the winged personification of death, is often depicted as a winged god.

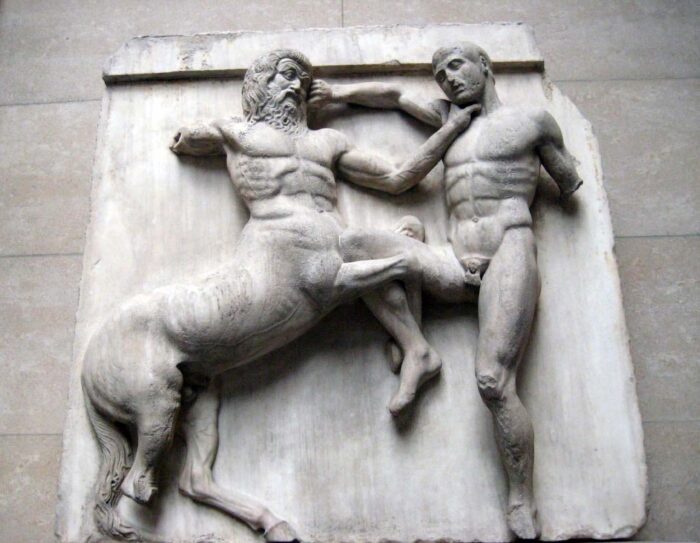

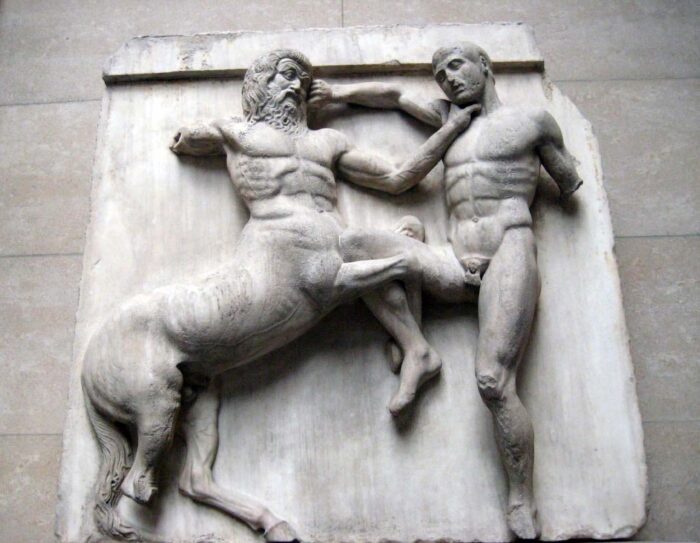

Centaurs

Centaurs were fascinating and complex mythical beings in Greek mythology, known for their unique combination of human and equine attributes.

Their dual nature and behavior made them compelling figures in mythology.

Here’s an expanded look at centaurs and their role in mythology:

Physical Characteristics

Centaurs were characterized by their hybrid anatomy, which consisted of the upper body of a human and the lower body of a horse. This striking fusion of two disparate creatures captured the imagination of ancient Greeks and continues to be an iconic image in mythology and art.

Origins and Nature

According to Greek mythology, centaurs were descended from Ixion, a mortal king who attempted to seduce Hera, the queen of the gods. As punishment for his audacity, Zeus created a cloud in the shape of Hera and placed it in Ixion’s bed. From this union, the first centaur, Centaurus, was born.

Centaurs were often portrayed as wild and unruly beings, torn between their human and equine instincts. This duality symbolized the struggle between civilization and the untamed wilderness.

Association with Wine

Centaurs were frequently depicted as indulging in wine and revelry, which often led to their aggressive and uncivilized behavior. One of the most famous stories involving centaurs is the Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs, which erupted at a wedding feast due to the centaurs’ drunken misconduct.

Conflict with Heroes

Centaurs often clashed with Greek heroes in mythological tales. These conflicts highlighted the tension between human virtue and the centaurs’ unruly nature.

One of the most notable encounters was the battle between Hercules (Heracles) and the centaurs, during which Hercules helped the Lapiths (a human tribe) defend themselves against the centaurs’ aggression.

Chiron – The Wise Centaur

While most centaurs were depicted as wild and unruly, Chiron stood out as a wise and noble exception. He was known for his wisdom, knowledge of medicine, and mentorship of Greek heroes, including Achilles and Jason.

Chiron’s unique characteristics set him apart from his fellow centaurs and made him a beloved and respected figure in Greek mythology.

Centaurs embodied the tension between the civilized and the primal aspects of human nature. Their dual nature symbolized the eternal struggle to balance our rational, human qualities with our instinctual and untamed side.

In this way, centaurs served as a reflection of the complex and multifaceted nature of humanity itself.

Their presence in Greek mythology added depth and nuance to the exploration of themes related to identity, civilization, and the challenges of navigating the human experience.

Harpies

Harpies were enigmatic and intriguing creatures in Greek mythology, known for their unique blend of avian and human features and their role as agents of divine punishment.

Their appearance, behavior, and mythological significance make them compelling figures in ancient Greek storytelling. Here’s an expanded look at harpies and their place in mythology:

Physical Characteristics

Harpies were typically depicted as female figures with the upper body of a woman and the lower body, wings, and talons of a bird. Their avian features included large wings, sharp claws, and sometimes feathered bodies.

The word “harpies” itself is derived from the Greek word “harpyiai,” which means “snatchers” or “swift robbers.” This name reflects their reputation for stealing and mischief.

Mischief-Makers and Punishers

Harpies were often portrayed as malevolent beings who caused chaos and disruption. Their primary role was to carry out divine punishment, particularly against those who had committed crimes or acts of impiety.

They were frequently sent by the gods, especially Zeus, to torment and punish individuals. One of their most famous targets was the seer Phineas, whom they plagued by stealing or defiling his food.

Symbols of Storms and Wind

In addition to their role as agents of punishment, harpies were sometimes associated with storms and winds. This connection to the elements further emphasized their wild and untamed nature.

In this capacity, they were thought to represent the unpredictable and often destructive forces of nature, particularly the fierce winds that could wreak havoc.

Transformation and Symbolism

Harpies embodied the idea of transformation and hybridity, a common theme in Greek mythology. Their blend of human and bird features symbolized the intersection of different realms and the complex interplay between the human and natural worlds.

Their ceaseless movement and predatory behavior served as a metaphor for the ever-changing and unpredictable aspects of life and fate.

Cultural Influence

Harpies have left a lasting impact on art, literature, and popular culture. They appear in various forms in classical and Renaissance art, as well as in works of literature such as Dante’s “Divine Comedy” and Shakespeare’s “The Tempest.”

In modern times, harpies continue to be featured in fantasy literature, films, and video games, where they often embody themes of chaos, vengeance, and the supernatural.

Harpies, with their distinctive appearance and dual role as both malevolent agents and symbolic creatures, added depth and complexity to Greek mythology. They served as a reminder of the capricious nature of the gods and the consequences of human actions. The enduring fascination with these winged creatures underscores their significance as enduring symbols in the world of mythology and storytelling.

Gorgons

The Gorgons, a trio of monstrous sisters in Greek mythology, consisted not only of the infamous Medusa, the only mortal, but also her sisters, Stheno and Euryale.

Together, they formed a fearsome and deadly group of beings known for their petrifying gazes and formidable abilities. Here’s a detailed exploration of each Gorgon sister:

- Medusa: Medusa was the most famous of the Gorgons. Her hair was made of venomous snakes. Anyone who looked directly into Medusa’s eyes would be instantly turned to stone. This deadly ability was a consequence of her transformation into a Gorgon as punishment for her affair with Poseidon in Athena’s temple. Medusa met her end at the hands of the hero Perseus, who, with the aid of divine gifts, managed to decapitate her while avoiding eye contact by looking at her reflection in a polished shield.

- Stheno: Stheno was the eldest of the Gorgon sisters and, unlike Medusa, was immortal. She shared Medusa’s petrifying gaze but lacked the vulnerability of mortality. Stheno was known for her fierce and unrelenting nature. She was a relentless and formidable figure, feared by both mortals and gods alike. While Stheno did not have the same level of notoriety as Medusa, her immortality made her a constant and enduring threat to those who crossed her path.

- Euryale: Euryale was the second of the Gorgon sisters and, like Stheno, was immortal. She possessed the same deadly gaze as her siblings. Euryale was often depicted as less fierce than Stheno, but equally dangerous. She was known for her beauty, which made her petrifying gaze all the more tragic for those who encountered her. Like Stheno, Euryale’s immortality ensured that she remained a formidable presence in Greek mythology, representing the inescapable and irreversible consequences of looking upon a Gorgon.

The Gorgon sisters collectively embodied the themes of mortality, danger, and the unknowable.

They were symbols of the perilous and mysterious aspects of the natural world, and their gaze was a powerful metaphor for the destructive potential of unchecked and uncontrolled forces.

While Medusa is the most renowned of the Gorgons due to her mortal status and her eventual confrontation with Perseus, Stheno, and Euryale served to reinforce the idea that the realm of the monstrous and supernatural was not limited to a single individual but extended to a fearsome trio of sisters.

Typhon – The Father of Monsters

Typhon was one of the most formidable beings in Greek mythology, known for his fearsome appearance and the terrifying offspring he fathered with the sea goddess Echidna.

These offspring, which included Cerberus, the Hydra, the Chimera, and Orthrus, were legendary creatures in their own right. Here’s an expanded look at Typhon and his notorious progeny:

Typhon was described as a colossal creature with a hundred serpent heads, eyes that spat fire, and a voice that roared like thunder. His head reached the stars, and his body spanned the earth.

Typhon was considered the deadliest threat to the Olympian gods, and his name was synonymous with chaos and destruction. He waged a cataclysmic battle against Zeus, the king of the gods, in an attempt to overthrow the Olympian order.

Offspring of Typhon and Echidna

Echidna, often referred to as the “Mother of All Monsters,” was a half-woman, half-serpent creature who bore Typhon’s monstrous progeny. Together, they created a lineage of creatures that terrorized both gods and mortals.

- Cerberus: Cerberus, often depicted as a three-headed dog with serpent-like tails, guarded the entrance to the Underworld. He guarded the Underworld, letting no soul escape or intrude. Hercules (Heracles) famously captured Cerberus as one of his Twelve Labors, demonstrating his unparalleled strength and bravery.

- The Hydra: The Hydra was a multi-headed serpent-like creature with regenerative abilities. For every head that was severed, two more would grow in its place. Hercules faced the Hydra as another of his Twelve Labors, cauterizing the stumps to prevent regrowth and ultimately defeating the beast.

- The Chimera: The Chimera was a hybrid creature with the body of a lion, the head of a goat on its back, and a serpent’s tail. A fire-breathing hybrid, the Chimera was a symbol of terror. Bellerophon, with the help of the winged horse Pegasus, defeated the Chimera in an epic battle.

- Orthrus: Orthrus was a two-headed, serpent-tailed dog, often depicted as the faithful hound of the giant Geryon. Heracles captured Orthrus during his Tenth Labor.

These monstrous offspring of Typhon and Echidna exemplified the chaos and danger that their parentage symbolized.

They served as formidable adversaries for Greek heroes, whose heroic deeds and triumphs over these creatures showcased their exceptional bravery and strength.

The tales of these creatures continue to captivate audiences and remain iconic elements of Greek mythology, representing the eternal struggle between order and chaos, civilization and the wild, and heroism in the face of formidable challenges.

Overall

The Greek pantheon, with its generations of gods and mythical beings, formed the foundation of ancient Greek beliefs and culture.

This rich tapestry of divine entities played a multifaceted role in shaping the ancient Greek worldview and collective identity. Here is an expanded exploration of how these mythic generations influenced Greek culture:

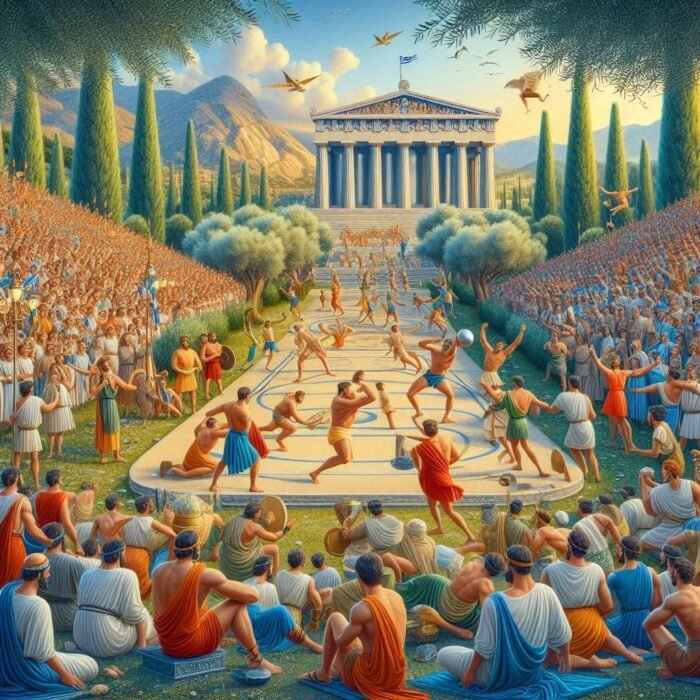

- Religious Beliefs: The Greek gods and goddesses were central to the religious beliefs of the ancient Greeks. Temples and sanctuaries were erected in their honor throughout Greece, and rituals, sacrifices, and festivals were held to appease or seek favor from the gods. Belief in the gods explained natural and celestial phenomena. The gods were seen as active participants in mortal affairs.

- Cultural Values: Greek mythology conveyed essential cultural values and norms. Stories of heroism, justice, honor, and hospitality were often intertwined with divine narratives. For instance, the heroic exploits of figures like Heracles and Achilles served as models of courage and virtue for the Greek populace. Morality and ethics were also explored through myths, with tales cautioning against hubris, impiety, and excess.

- Art and Literature: Greek mythology had a profound influence on the arts, including sculpture, painting, drama, and literature. Mythological themes and characters were common subjects for artists and writers, yielding masterpieces like the sculptures of the Parthenon and epic poems like Homer’s “Iliad” and “Odyssey.” Dramatic plays, particularly tragedies and comedies, frequently drew inspiration from Greek myths, serving both as entertainment and a means of philosophical and moral reflection.

- Political and Social Structures: Greek city-states often had patron deities and heroes associated with their founding or protection. These figures played a role in civic identity and governance. Social institutions, such as marriage and hospitality, were influenced by myths and rituals associated with gods and goddesses.

- Education and Philosophy: Greek philosophers, including Plato and Aristotle, explored the nature of the divine and the cosmos through the lens of mythology. Myths were used to illustrate philosophical concepts and moral dilemmas. Mythology was a crucial component of Greek education, as it conveyed important cultural and moral lessons to young citizens.

- Exploration of Human Nature: Greek myths often delved into the complexities of human nature and the human condition. They explored themes of love, jealousy, ambition, and mortality. The gods and heroes were not without flaws, and their stories showcased the triumphs and tribulations of both mortals and immortals, making them relatable figures.

- Continued Influence: Greek mythology continues to exert a profound influence on modern Western culture. It has been adapted, reinterpreted, and incorporated into literature, art, film, and popular culture.

Greek myths and archetypes remain iconic, offering a universal language for storytelling and exploring human nature.

Comments